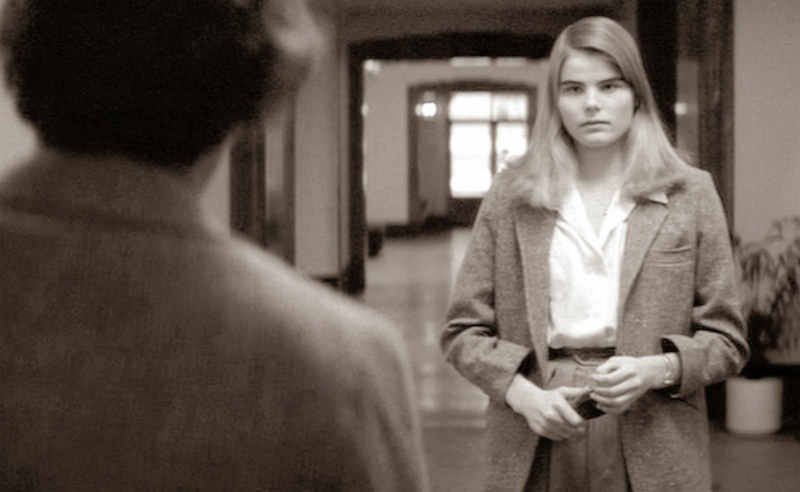

Mariel Hemingway as

Tracy in

Manhattan (1979)

by Ted Mcloof

In the autumn of 2009, when our relationship began, I can hardly remember doing anything else besides talking to Jax. We were the kind of twentysomethings who were discovering some hard truths about the world, and believed we were the only two twentysomethings who had ever discovered them. The subject of our conversations was almost exclusively love, or more specifically the elusive nature of it: we were both the children of messy divorces and were, consciously or not, working through heavy commitment issues. These talks took the form of debates, but the mutual language we spoke, the one we turned to whenever we wanted to prove a point to the other, was movies.

In the autumn of 2009, when our relationship began, I can hardly remember doing anything else besides talking to Jax. We were the kind of twentysomethings who were discovering some hard truths about the world, and believed we were the only two twentysomethings who had ever discovered them. The subject of our conversations was almost exclusively love, or more specifically the elusive nature of it: we were both the children of messy divorces and were, consciously or not, working through heavy commitment issues. These talks took the form of debates, but the mutual language we spoke, the one we turned to whenever we wanted to prove a point to the other, was movies.

Obsessed as we were with the question of how to love unselfishly and why neither of us were comfortable accepting affection, Woody Allen, naturally, was both of our favorite filmmaker. We saw ourselves as Allen characters. Jax, who often found herself “sure only of what she didn’t want,” identified with Vicky, Scarlett Johannsen’s capricious romantic in Vicky Cristina Barcelona. Alvy Singer, Allen’s character in Annie Hall, describes his romantic life by paraphrasing Groucho’s thing about not wanting to “belong to any club that would have me as a member”, which resonated with my own self-loathing. As any of Allen’s Freudian movie-psychologists would point out, Jax and I had had needy mothers growing up, but we reacted to them in diametrically opposite ways. Jax rejected the emotional drain of others’ needs by concentrating primarily on the Self as a pathway to mental health (hence her preoccupation with what she did and didn’t want). My own mother had drilled into me that it’s vital to put others first (hence the self-loathing). Our yin-yang internalizations of the same basic upbringing has always seemed to me a result of her being a West Coaster (new age, self-help, yogi) and me an East Coaster (no-bullshit, self-critical, chainsmoker), a bicoastal dichotomy Woody Allen has mined many times for comedy in his films.

Allen’s films are neurotic balm for the neurotic heart, probably because they’re more content to offer food for thought than actual answers. Neurotics are emotional hypochondriacs. We don’t want cures for our neuroses—or, rather, we claim to want cures but feel much more soothed by talking about them endlessly. Endless talk was the source of nourishment for our relationship, and so Jax and I hoovered up Allen’s oeuvre. Shockingly, though, Jax had never seen my favorite film and what I would call Allen’s seminal masterpiece, Manhattan. So we drove off to Blockbuster (Blockbuster!) in the rain one Friday afternoon to rectify the situation immediately.

~

Manhattan, perhaps more than any other Woody Allen film, is plotless. As Allen’s character Isaac says, in a meta-commentary in the penultimate scene, the film is about “people in Manhattan who are constantly creating these real, unnecessary, neurotic problems for themselves because it keeps them from dealing with more unsolvable, terrifying problems about the universe.” True to that description, Allen’s Manhattanites swap romantic partners like whack-a-mole, having affairs, getting tired of those affairs, ending them, only to get nostalgic and return to their lovers. Isaac’s second wife Jill (Meryl Streep) has left him for a woman, and Jill is writing a tell-all book about their marriage. Isaac is naturally distressed about this, but even this fraught situation is played more as the characters causing this frenzy than dealing with it (Streep, in a typically note-perfect performance, dryly reacts to Isaac’s nebbish protests, as if to suggest he’d cause the same fuss over an undercooked meal).

Yale (Michael Murphy) declares his infatuation with Mary (Diane Keaton) in the second scene of the film; by twenty minutes in, they’ve grown bored of each other, and are already looking to rope Isaac in as a way of solving the mess they’ve gotten themselves into. Isaac and Mary at first loathe each other: Mary is an unabashed snob, happily dismissing the likes of Mahler, Fitzgerald, and Bergman as “overrated,” and Isaac is an intellectual populist (note that in his opening monologue, he dials back on writing about moral decay because it’s “too preachy, I mean, let's face it, I wanna sell some books here”). It’s important to note that, when they do eventually bond, they pretty much bond over the fact that they overthink everything (Mary worries Isaac thinks she’s “too cerebral,” but that’s precisely why he suspects she’s a kindred spirit).

The point here is that Manhattan is a pure example of Allen’s kind of characters, characters who overintellectualize everything to the point of anhedonia (Anhedonia was, in fact, Allen’s original title for Annie Hall). The verisimilitude of these characters’ pedantry is why neurotics are such devotees, and why normal, healthy people tend to be irritated by the Allen universe.

But then, somewhere among the woman whose analyst told her she’s been “having the wrong kind of orgasms,” the black-tie cocktail parties, and the steel cube at the Guggenheim that had a “perfectly integrated, marvelous negative capability,” Mariel Hemingway’s Tracy emerges, and all of these people’s talk sounds like exactly what it is: bullshit.

~

For a while, Jax and I had arguments about who Tracy was and how she fit into the film. Like the characters in Manhattan itself, we were a little disarmed by her presence. Tracy, for one thing, is seventeen. It isn’t enough to just say she doesn’t act it—she does, or rather, she acts like herself, and one thing that herself is is seventeen. But her age puts her in stark contrast to the adults she surrounds herself with, the kind of adults who spend their weekends at the Hayden Planetarium and whose analysts recommend dogs as penis substitutes. Tracy establishes herself as a presence in all of their conversations, even when she isn’t speaking.  As Roger Ebert points out, that even extends to the physical: “[Hemingway] is, of course, taller than Allen, but the meaning of that difference is not as simple as the tall girl-short guy syndrome. Seeing them together on the screen, I was struck by how unconcealable she is, how her presence is such an inescapable fact.”

As Roger Ebert points out, that even extends to the physical: “[Hemingway] is, of course, taller than Allen, but the meaning of that difference is not as simple as the tall girl-short guy syndrome. Seeing them together on the screen, I was struck by how unconcealable she is, how her presence is such an inescapable fact.”

Tracy chooses not to participate in Mary’s argument against nihilism (“don't you guys see that it is the dignifying of one's own psychological and sexual hang-ups by attaching them to these grandiose philosophical issues?”), nor does she come to Isaac’s aid when he attempts to rebut it and mock Mary’s pronunciation of Van Gogh (“Van Goch? Did you hear her?”). And this, again, is where we get into the neurotic’s love of Allen’s films. It’s easy for them to assume, as Isaac does, that Tracy abstains from comment because the conversation is above her head (being in high school and all). It’s easy for them to look at this person who listens in a world of endless talk and think she has nothing to say. And yet Allen never lets them (us) off the hook that easily, never simply creates wish-fulfillment fantasies or flatters the core demographic. Because he takes the smug neurotic’s assumption that the unanalytical peons surrounding us are lesser-than and exposes what a thin defense mechanism that is.

Certainly Jax and I mistook Tracy as one such unanalytical peon in our conversations. For a while, we took it as a given that Tracy was “simple” while Mary was “complicated,” and often used their names as placeholders for a certain kind of romantic partner (as in, “She got sick of the dramatics and unpredictability, so she married a Tracy”; “I know I can be exhausting sometimes, but that’s because I’m a Mary…” etc). We spent a lot of time arguing over whether it was saner to end up with someone who frustrates, but challenges, you (Mary) or someone who makes you feel safe, but isn’t your equal (Tracy). We were, of course, really talking about each other and our own future, but using these characters as a secret code allowed us to confront our relationship’s decay without having to name it outright.

~

Maybe it would have helped had we not both so horribly misread this character’s role, her substance, her point. In examining that point, I’m wary of muddying the waters, especially for those who have only a passing familiarity with Allen’s films, and especially for those who know him better from tabloids than from his art. (I have a giant poster of Isaac speaking into a tape recorder in my living room, and, looking at my film collection just now, notice that I own twenty-three of his films. Trust me, I know I’m not an objective source here). I’m especially nervous that, writing this in the aftermath of Nathan Rabin’s coining of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, I might make Tracy sound like such an archetype to the casual viewer. Rabin eventually apologized for this term’s overuse, naming, among other characters, Annie Hall as an example of a more complex woman than such a dismissive term gives her credit for: “Allen based a lot of Annie Hall on Diane Keaton, who, as far as I know, is a real person and not a ridiculous male fantasy” he points out, and Tracy, too, was based on the real-life Stacey Nelkin. Having dated Nelkin—and many other younger shiksas since—and having cast Hemingway, who looks very much like the type of young woman who could eliminate a sadsack’s neuroses, Allen might forgive his critics for approaching Tracy with caution. But his present-day reputation shouldn’t blind us to the fact that Allen-the-artist’s women have always been complex and intelligent and independent, and, to quote Ebert again, “Allen's real-life partners, from Louise Lasser through Diane Keaton and Mia Farrow to the Soon-Yi Previn seen in the 1998 documentary "Wild Man Blues," have all been assertive and verbal.”

True, Tracy gives Isaac a harmonica in an effort to “open up that side” of him, but she’s hardly defined by their relationship. She’s not some lively sprite whose job it is to cheer up our hero and then fade into the darkness. Far from being naïve, Tracy is probably the wisest person in the film. When Emily and Isaac and Yale dominate the conversation at Elaine’s Restaurant in the opening scene, Tracy doesn’t weigh in on their debate about talent vs. courage, and it’s not because she doesn’t get it. It’s because she sees these people for exactly who they are. She intuits what Isaac takes the whole film to realize, which is that these characters’ inability to shut up is a defense mechanism against their own fears. Tracy has no such fears, and therefore feels no need to pontificate alongside the other people in the Allen universe. Tracy knows instinctively, as Isaac only eventually discovers, what Empire’s David Parkinson calls “the empty decadence of the city's chattering classes in much the same way that [La Dolce Vita’s] Marcello realized the moral and intellectual bankruptcy of Rome's elite.” She’s actually a corrective to the psychobabble that turns functional people off of Allen’s films. She’s intelligent, game to discuss those exhibits in the Guggenheim, interested in photography and drama, ready by the end of the film to study theater in London. She loves Isaac, and is sad when their relationship ends, but is just as comfortable moving on when he breaks up with her. It’s especially noteworthy that she’s so comfortable moving on—in contrast to these partner-swapping “adults”—that she exits the film to do her own thing for a half an hour while the supposedly mature characters continue to kvetch and quibble and vacillate.

Isaac breaks up with Tracy a lot in the film, because he, like the other characters (and like Jax and I) dismisses her as too innocent. Mary calls her “the little girl,” and Isaac continually tells her she’s “just a kid” and shouldn’t get hung up on him. “You won’t take me seriously,” she has to protest to him throughout the film. And she’s right—the other characters are far too busy listening to the sound of their own voices to recognize that Tracy’s never actually given them any reason not to take her seriously. She gives as good as she gets, teasing Isaac by pretending she doesn’t know who Rita Hayworth is and telling him to stop assuming she doesn’t “get any references pre-Paul McCartney.”

This was the truth about Tracy, and by extension about relationships, that Jax and I had failed to recognize at the time. We’d so convinced ourselves that smart people were the ones who kept themselves up at night with self-analysis that we’d never considered that those who slept soundly not only might be just as enlightened as us, but that in fact they might know far more. We had stubbornly convinced ourselves that a relationship didn’t have value unless it drove you nuts, so of course we looked at Tracy—who plays it straight, tells people that she loves them when she does, only to be met with the condescending admonition that “You don’t know what that means”—as a dilettante. We were, in other words, doing what Allen’s characters do: avoiding the reality of our situation, our fears, the larger questions, and assuming that those who didn’t do likewise were simple, even though there was ample evidence that our healthier counterparts were probably more evolved than either of us.

As KM Soehnlein says in The Film Experience, Tracy is “the most emotionally well-adjusted 17-year-old ever… she’s the only grown-up among all these stunted adults.”

~

Hemingway was the same age as her character at the time of production, and had to become an incredibly well-adjusted seventeen-year-old herself, as her Oscar nomination here catapulted her into a career she hadn’t anticipated. In her memoir, she talks about the realization that she was going to have to make her own choices after Manhattan’s success, because she was officially a legal adult (as Tracy becomes at the end of the film) and her parents weren’t going to help her out. In a case of life imitating art, Woody Allen had developed a crush on her during filming and, as Isaac does with Tracy in the film, came to her house to take her to Europe.

Hemingway declined the offer, because she wasn’t interested, and she and Allen remained friends (she later appears in 1997’s Deconstructing Harry). But when Hemingway relayed this anecdote in her memoir, nearly every media outlet reporting on her book headlined the story “Woody Allen Tried to Seduce Mariel Hemingway When She was 18.” The instinct of the press was to infantilize her, to protect this naive, innocent girl and call out her would-be seducer.

But Hemingway herself was taken aback by the reaction, having not remotely intended the anecdote to be taken that way. "The whole point of telling that story is not to say, ‘isn't Woody Allen creepy.’ It was to say that I always had to find my own voice,” she said in response. “My parents weren't going to step up and say, 'I'm sorry Mr. Allen, you're too old for our then 18-year-old daughter.' It was never up to anyone else. It was always up to me to find my voice."

In real life, as in the film, the people who presume to know more than Hemingway/Tracy and do what’s in her best interests (as Isaac does by ending their relationship to spare her feelings) ironically end up being the ones who dismiss her humanity in the name of their own moral superiority.

But that’s far too reductive. The finale of the film finds Isaac recognizing that avoiding life’s big questions also means avoiding that which makes life worth living (Tracy chief on that list, along with Sentimental Education and Louis Armstrong’s recording of “Potato Head Blues”), and rushing to share this epiphany with her. But Tracy’s headed to London, having resigned herself to their relationship’s end and moved on. “Stop being so mature,” he tells her, in a complete reversal of his usual insistence that she’s too young—but of course Tracy hasn’t changed (she’s behaving exactly as she has in the rest of the film) as much as Isaac is, for the first time, taking her seriously. She’s genuinely appreciative of his declaration of love, but isn’t going to change her plans for him, because Tracy is not a savior or a MPDG or anything else that has to do with Isaac. She’s Tracy, the only guileless, level-headed person in a sea of neurotics. “Not everybody gets corrupted,” she says in the last line of the film, a sentiment I so often have to remind myself of that I got it tattooed on my forearm, “you have to have a little faith in people.” A simple sentiment, yes, but just because these words are simple doesn’t mean they aren’t true.

But that’s far too reductive. The finale of the film finds Isaac recognizing that avoiding life’s big questions also means avoiding that which makes life worth living (Tracy chief on that list, along with Sentimental Education and Louis Armstrong’s recording of “Potato Head Blues”), and rushing to share this epiphany with her. But Tracy’s headed to London, having resigned herself to their relationship’s end and moved on. “Stop being so mature,” he tells her, in a complete reversal of his usual insistence that she’s too young—but of course Tracy hasn’t changed (she’s behaving exactly as she has in the rest of the film) as much as Isaac is, for the first time, taking her seriously. She’s genuinely appreciative of his declaration of love, but isn’t going to change her plans for him, because Tracy is not a savior or a MPDG or anything else that has to do with Isaac. She’s Tracy, the only guileless, level-headed person in a sea of neurotics. “Not everybody gets corrupted,” she says in the last line of the film, a sentiment I so often have to remind myself of that I got it tattooed on my forearm, “you have to have a little faith in people.” A simple sentiment, yes, but just because these words are simple doesn’t mean they aren’t true.

~

Jax and I eventually went our separate ways. Going back to Vicky Cristina Barcelona, we didn’t know what we wanted, but we knew that what we didn’t want was each other (or anyway, the thing we valued in each other was that we stimulated, and thus validated, the other’s neuroses, like a romantic version of Munchausen-by-proxy). Like Mary and Yale and Isaac, I spent a few years breaking up with partners whose only fault was that they weren’t Jax, and Jax had a similar road, though, of course, whenever we tried to get together again it was never as good as when we were pining for each other.

I don’t think we ever admitted that at the time. I’m not sure I ever admitted it to myself before writing this. Like the media, which used Hemingway’s story to sell papers, and Isaac, who projects onto Tracy a happy ending for himself regardless of her plans, it’s possible that I similarly used this character to learn how to be in a functional relationship and sleep soundly (which I am and do now). It’s probable that, lacking the vocabulary to articulate this lesson to myself, I branded myself with this character’s dialogue and mined her experiences to fit my own needs, rather than just allowed her to exist as her own person. I find myself hoping that she’s off in London somewhere, enjoying the theater, living her life without losing faith. She deserves to be taken seriously.

Ted McLoof teaches English at the University of Arizona, and fiction/screenwriting at the University of Arizona Poetry Center. His work has appeared in Bellevue Literary Review, Minnesota Review, Hobart, DIAGRAM, Louisville Review, The Rumpus, Monkeybicycle, Kenyon Review, and elsewhere. Pretty much all of said work, and all conversation with him, is about what you just read: neuroses, relationships, and film. He returns to his home state of New Jersey twice a year to spend a week quoting movies with his best friend Melissa.

Ted McLoof teaches English at the University of Arizona, and fiction/screenwriting at the University of Arizona Poetry Center. His work has appeared in Bellevue Literary Review, Minnesota Review, Hobart, DIAGRAM, Louisville Review, The Rumpus, Monkeybicycle, Kenyon Review, and elsewhere. Pretty much all of said work, and all conversation with him, is about what you just read: neuroses, relationships, and film. He returns to his home state of New Jersey twice a year to spend a week quoting movies with his best friend Melissa.

~