Werewolf Jones in

Simon Hanselmann’s

Megg, Mogg, and Owl (2009-2017?)

by Madeline Gobbo

Before we begin, you should know that Werewolf Jones will die on Christmas of this year. He will overdose, alone, having just ejaculated into a friend’s mattress. No one will discover him for hours. When his friends get the news, collapsed on their crusty couch, it won’t surprise them in the least.

Before we begin, you should know that Werewolf Jones will die on Christmas of this year. He will overdose, alone, having just ejaculated into a friend’s mattress. No one will discover him for hours. When his friends get the news, collapsed on their crusty couch, it won’t surprise them in the least.

Of course, you don’t really have to be sad, because Werewolf Jones is neither human nor three-dimensional—he’s a cartoon character, one of many hapless monsters roaming the pages of Simon Hanselmann’s ongoing comics series, variously known as Megg, Mogg and Owl; Megg and Mogg; Life Zone; and Truth Zone (sometimes drawn by HTML Flowers), and compiled in the graphic novels Megahex and Megg and Mogg in Amsterdam. Hanselmann has not yet published this arc, ominously titled “Xmas 2017,” but rumors of it have been circulating on the internet since 2015, when Hanselmann posted the first page of the comic on his Tumblr (the post has since been removed). Megg, Mogg and Owl cuts its pastiche of druggy hijinks with blackest ennui, but with the death of Werewolf Jones the series becomes true tragicomedy. This is Trainspotting’s baby on the ceiling, the “final humiliation” of Peep Show’s sixth season, the big comedown after the transcendent but unsatisfying high.

Focused on the lives of three extremely unmotivated roommates in a dumpy house in the suburbs, Megg, Mogg and Owl depicts small (and large) acts of cruelty between miserable creatures. Though our heroes are played by a depressed stoner witch, her black cat familiar/boyfriend, and a persnickety owl in a tie, they manage to be both relatable and (mostly) sympathetic. But the comic doesn’t stay in the real world much. There are far too many drugs for that, and then there’s Werewolf Jones.

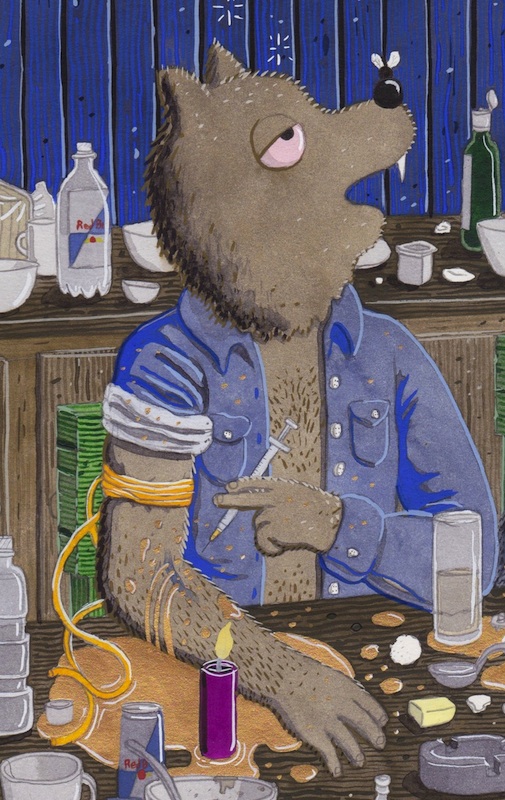

After the titular trio, Werewolf Jones is the character who appears most frequently. The fact that his name is not included in any of Hanselmann’s titles (save the standalone zine Werewolf Jones & Sons), would likely piss him off in the extreme. Though his name indicates full lycanthropic powers, his body is stuck mid-transmogrification, so he has a wolf’s head and a gray, filthy, human body (and dick).  WWJ is more accurately described as a cynocephalus: a dog-headed man, unable to commit to life as either man or beast. WWJ’s hangdog features beg you to forgive him. He knows not what he does. He’s a monster, and it’s always the full moon. He is very very sorry.

WWJ is more accurately described as a cynocephalus: a dog-headed man, unable to commit to life as either man or beast. WWJ’s hangdog features beg you to forgive him. He knows not what he does. He’s a monster, and it’s always the full moon. He is very very sorry.

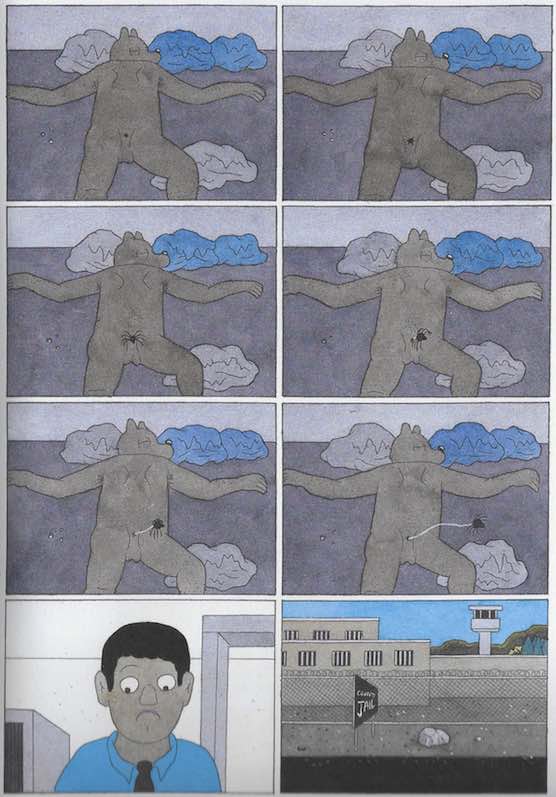

This self-harming party animal is the spawn of the sitcom wildcard. He’s Kramer on literal PCP. It’s no coincidence that his last name is Jones. One gets the sense that he crashed one of the trio’s keggers early on and simply never left. Werewolf Jones spends more time in Megg, Mogg and Owl’s house than they do, playing video games, dealing drugs, and trying to manage partial custody of his terrifying sons, Jaxon and Diesel. When the roommates leave for Amsterdam, Werewolf Jones finally declares squatter’s rights and renames the residence “The Fuck Zone.” When the zone is disbanded upon Owl’s return, no problem: Werewolf simply packs up his sons in two trashbags and tries to hop a plane to Amsterdam. This leads to what is possibly the series’ all-time greatest sight gag: after being stopped by TSA agents and hit hard by the cocktail of mile-high barbiturates he’s taken to endure the long flight, WWJ strips nude and demands the agents inspect his butthole for drugs. He promptly passes out. We watch, for the space of nine frames, as said butthole reveals itself to be a spider, who seizes the chance to belay the hell out of that unspeakable place.

I recommended Megahex to a bookseller friend who told me he couldn’t finish reading it. He identified with Owl: the innocent, fussy indoor kid, the butt of his friends’ mean jokes. “Owl’s Birthday” is a particularly damning episode for readers who are still trying to find a shred of likeability in these characters. Megg and Mogg drug Owl (more than usual) and meet Werewolf Jones at an undisclosed location. They usher Owl into an empty room and close the door. Mogg tells Owl they’re going to “do” him. The assault begins as a 3-on-1 suckerpunch and ends with Werewolf Jones mashing his flaccid dick against Owl’s ass. So, I understand my friend’s reaction. Owl takes a lot of shit simply because he can still be bothered to care about mundane things like birthdays and clean dishes and whether or not dickmashing constitutes rape.

Despite his utter disrespect for his friends’ property, consent, or personal integrity, WWJ is never conclusively banished from their social circle. The reason for their attachment is simple. WWJ is the consummate masochist, willing to resort to humiliating and painful lengths to secure the attention and amusement of his three wasted friends, and anyone else in eyeshot. In his first appearance in Megahex, he nicks an artery in a drunken attempt to cheese-grate his balls. His final words before being carried off in the ambulance are: “Don’t stop the party! I’ll be back in an hour!” We recognize these antics. He’s a loveable weirdo, caught under the warped cartoon glass. Where some see recklessness, others see freedom, a refusal to bow to respectability or to integrate with the mundane.

“I get letters from people who have crushes on Werewolf Jones,” Hanselmann remarked in an interview with Hazlitt. “‘I love Werewolf Jones, he’s so cool, I want to date him!’ And I say, ‘Really? Jesus.’”

“I get letters from people who have crushes on Werewolf Jones,” Hanselmann remarked in an interview with Hazlitt. “‘I love Werewolf Jones, he’s so cool, I want to date him!’ And I say, ‘Really? Jesus.’”

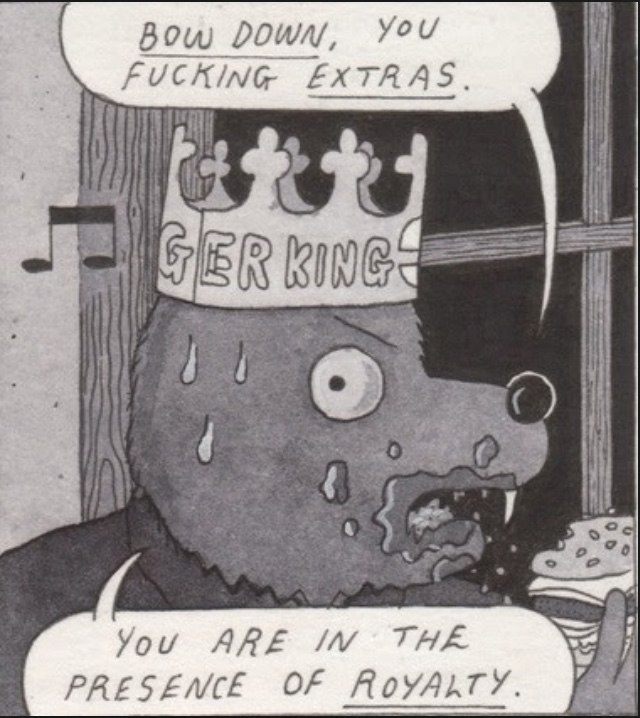

Consumers of pop culture have been conditioned to cheer for characters like Werewolf Jones. We see them as larger than life: untamed, mythic figures of debauchery. We applaud their eccentricities and dismiss their darkness; we don’t consider the sort of damage that might spur a college kid to chug a whole bottle of vodka for laughs. WWJ’s invasion of Owl’s closet to convert it into a Gatorade-fueled sauna recalls the time Kramer installed a working Jacuzzi in his own tiny apartment. Kramer boiled in his own butter and Newman considered cannibalism to a canned laugh track. WWJ’s DNA is at least 50% Kramer. Both are ravenous wackos prone to dramatic entrances. Both are more comfortable in criminal circles than civilized ones, but no matter how far into the underworld he travels, Kramer always retains his basic likeability. Other characters treat him like a poorly-trained pet, indulging his more harmless eccentricities and scolding him when he spins too far out of control. In “The Bubble,” one of my favorite episodes, Kramer burns down an entire cabin with a misplaced Cuban cigar. But it’s George and Susan who take the brunt of the blame in the following episode. Kramer doesn’t even show up to dinner to apologize.

Still, there’s some part of us that thinks characters like Kramer “aren’t so bad.” They are. They are so bad. WWJ literalizes this dynamic and lays bare its dysfunctionality. Hanselmann’s cartoon world gains moral ascendancy over the multicam sitcom in its insistence on keeping the camera rolling for the consequences, both material and emotional. And Hanselmann’s characters are undeniably miserable. Owl’s pettiness, Mogg’s malaise, Megg’s “daily body freakout”: every ounce of self-loathing swings the door open wider for Werewolf Jones and his brand of chaos.

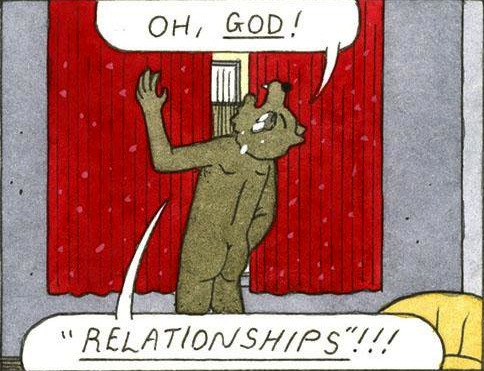

I’m uncomfortable with many—most of Werewolf Jones’s actions, but Hanselmann provides us with a scenario in which his chaotic violence is a proportional reaction to the oppressively ordinary world he inhabits. Hanselmann grew up in a small town in the remote state of Tasmania, and the environment of Megg, Mogg and Owl replicates that parochial scumminess in perfect detail. The 7-11s, video rental stores, and fluorescent mini-malls stocked with unfashionable and useless goods represent a stark realism in direct contrast with the chimeras who inhabit them. Apart from the core cast of Megg, Mogg and Owl and their social circle—who present as transgressive figures such as vampires, bogeymen, and robots—the “extras” in the MMO world are recognizable as human, even though they all share the same bug-eyed potato face. The visual starkness of this juxtaposition makes it difficult to say who’s transgressing on who. Were the supernatural characters spawned by the mundanity of life or have they been transported into it against their wills? In the second scenario, the reader can sympathize with the characters’ desire to destroy either the whole world or themselves, as quickly as possible. In the first scenario, Hanselmann is issuing a warning. If things keep going this way, we’re all in danger of wolfing out.

A short list of the crimes committed by this character would surely include:

Home Invasion

Squatting

Public Indecency

Public Drunkenness

Indecent Exposure

Indecent Exposure at an Airport

Public Urination

Urination on Private Property

Assault with Urine

Theft

Simulated Rape

Statutory Rape

Sexual intimidation

Human trafficking

Embezzlement

Child Abuse

Child Endangerment

Child Labor Violations

Child Pornography

Arson

I have no doubt that WWJ’s sitcom predecessors have rap sheets just as long, or longer, but in their worlds, these crimes go unpunished, and are often completely forgotten by the next episode. Although MMO is a cartoon universe, it maintains a moral integrity that is never present in sitcoms. There’s a memento mori in every acid trip, illicit blowjob, and suicidal party stunt. Megg, Mogg, and Owl have their bouts of hedonism, depression and cruelty, but for each of them there exists the window of redemption we’ve granted to other sitcom misanthropes. Werewolf Jones presents a notable exception. Despite his slapstick—or maybe because of it—he never, ever escapes blame for his actions. Cartoons have a long history of constructing internally consistent moral worlds: it’s not a stretch to see WWJ’s dilemma as stemming from the purgatorio of Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote. Wile E., another lycanthrope, is industrious, inventive, and earnest; a true believer if there ever was one. But his status as a predator can never be forgiven, and at the end of each episode he must be punished. This punishment reinforces the laws of the Looney Tunes universe, frees the viewer from moral analysis and allows for pleasurable escape. But WWJ’s world commits to neither predestination or total nihilism, and that is what makes it recognizable. No matter how unlikeable he is, WWJ’s death has impact because he’s one of our own.

As you read Hanselmann’s gorgeous comics, it’s frighteningly easy to forget that Werewolf Jones is a lecherous slimebucket. Moment to moment, he can be fun, funny, whimsical, loyal, compassionate, courageous, tender, open-hearted, and self-aware, just like us. Werewolf Jones cries at the drop of a hat. Werewolf Jones dreams of opening a father-and-son felted hat shop. Werewolf Jones just wants to be a good dad. Can these qualities coexist with the above list of violations? Are they Werewolf Jones’s delusions, or are they our own? WWJ’s prophesied demise is only a feint towards morality—a calling out of the reader’s conditioned and reductive desire to see the contradictions of WWJ’s personality resolved. In the absence of Seinfeldian permissiveness or Looney Tunes’s unyielding karma, Hanselmann gives us only a crumb of justice, enough to see that the whole system is flawed.

Hanselmann thinks of his characters as extensions or excisions of himself. He’s noted that if he had to identify with just one, he’d choose Megg, but the honest answer is probably Werewolf Jones.

“He doesn’t change. He ruins himself. I feel very self-destructive sometimes, and that comic is a reminder to myself to change before it’s too late.”

“He doesn’t change. He ruins himself. I feel very self-destructive sometimes, and that comic is a reminder to myself to change before it’s too late.”

I’m not sure whether knowing Werewolf Jones’s doom will change every reader’s perspective, but as I reread these comics I watched his antics with increased focus, even poignancy. In the past year, I’ve known two young men whose deaths could’ve been written for Werewolf Jones. One was trapped in a fire at a warehouse party; the other overdosed in the bathroom of a Lower East Side bar.

In eulogies, people talked about both of these young men as having been “taken too soon.” That language struck me as odd. Of course we don’t want anyone to die young, but to die “too soon” implies a chronological framework to existence, something this two men should’ve held out for, stayed strong against temptation, kept back from uninspected buildings. This is the same fallacy that allows us to love sitcoms: to laugh at them we must believe that the ups and downs of life will ultimately average out to baseline. It allows us to forgive ourselves for not having reached out sooner, for forgetting to call, for waving off the latest slight, thinking, “It’ll all blow over in the morning.” WWJ supposes it might not, and in this cruel reality it’s never too soon to give in to the gale.

I like to think that I remember my friends in the way Megg, Mogg and Owl will think of Werewolf Jones after his exit. Death might seem like the appropriate punishment for someone as despicable as WWJ, but in the aftermath, his unending absence from MMO’s comic rhythms will swallow up whatever flimsy moral structure the readers might cobble together to justify it. Each time my friends pass through my thoughts, which is often, it’s as though I’ve missed a step, or come up against a hairline crack in reality. Their disappearances have been transmuted into a thousand apparitions which can transfix me at any time of day. My hope is that MMO post-”Xmas 2017” will reflect this experience. The absence of WWJ’s name from the title, once a joke, could become a space into which he might still return, in one form or another.

I wonder why Hanselmann felt he had to write, in Werewolf Jones, a “reminder.” Is it fair to designate a character to carry the entire weight of consequence in the MMO world as well as in the mind of his creator? People die all the time and it doesn’t mean anything but death itself, that precipitous drop from existence to nonexistence. But fairness doesn’t seem to be the question that interests Hanselmann. As readers, we don’t get to decide which characters affect us. We aren’t only nourished by tales of redemption and true love. Though each reader comes to MMO with her own set of convictions and principles, Hanselmann points out that we aren’t really asking how we should exist but whether we should. The sad story of Werewolf Jones powerfully demonstrates art’s ability to remind us of our shared and infinite struggle not to self-destruct.

Madeline L. Gobbo (born 1990) is an American writer and illustrator. She was born and raised in Hood River, Oregon, and is the daughter of an ob/gyn and a renaissance woman. Her ancestry is Italian AF. In 1995, Madeline wrote a series of picture books about crime-solving donkeys, and by age 26, she had entered the graduate writing program at UC Davis.

Madeline L. Gobbo (born 1990) is an American writer and illustrator. She was born and raised in Hood River, Oregon, and is the daughter of an ob/gyn and a renaissance woman. Her ancestry is Italian AF. In 1995, Madeline wrote a series of picture books about crime-solving donkeys, and by age 26, she had entered the graduate writing program at UC Davis.

Her work has appeared in Queen Mob's Teahouse, Cosmonauts Avenue, and Black Candies: Gross and Unlikeable, for which she was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Her illustrations appear in Loose Lips, an anthology of erotic literary fanfiction, and Texts from Jane Eyre, by Mallory Ortberg. Her collaborative fiction with Miles Klee appears in McSweeney's Internet Tendency, Funhouse, Another Chicago, Hexus, Wigleaf, Joyland, Arcturus, and Territory.

~