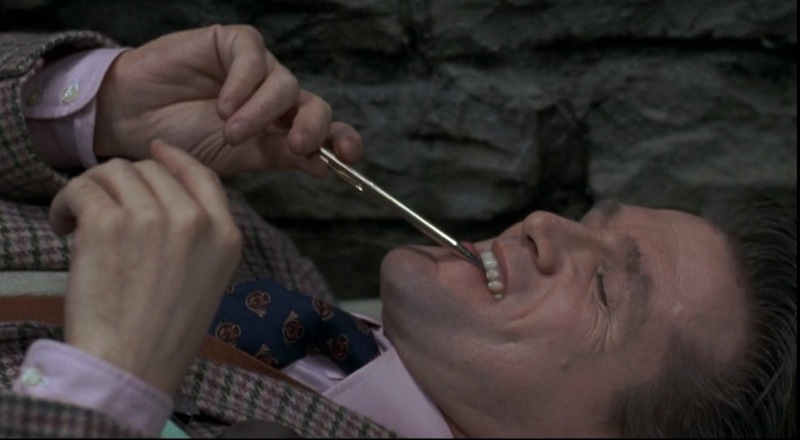

Anthony Heald as

Dr. Frederick Chilton in

Silence of the Lambs (1991)

by Lewis DeJong

Jonathan Demme passed away recently, leaving behind a formidable filmography. The remembrances that’ve rolled in since extol his tireless enthusiasm and versatility across genres. The more astute critics have discussed his advocacy for the American outcast. This echoes the International Dictionary of Films and Filmmakers where Norman Miller suggests that “Demme’s concern with character—focused particularly through the observation of telling eccentricities—is perhaps his trademark.”

Jonathan Demme passed away recently, leaving behind a formidable filmography. The remembrances that’ve rolled in since extol his tireless enthusiasm and versatility across genres. The more astute critics have discussed his advocacy for the American outcast. This echoes the International Dictionary of Films and Filmmakers where Norman Miller suggests that “Demme’s concern with character—focused particularly through the observation of telling eccentricities—is perhaps his trademark.”

My favorite movies of his attempt to bring unlikely worlds together. In his early highlights, Married to the Mob placed a mafia widow back into workaday New York and the right side of the law, and Something Wild sent a starched shirt banker on a dangerous search for his feelings. Later, Philadelphia would bring the plights of AIDS victims into a public discussion, and Rachel Getting Married pits a reckless addict against the decorum of family events. He even took on the task of presenting David Byrne’s eclectic tastes to the mainstream. These are collisions but productive ones. The end results imply a sense of optimism and justice.

The Silence of the Lambs, however, has a fraught relationship to hope and fair play. It’s a grisly movie. The procedural part is violent enough on its own, not to mention there is serial killer on the loose and a cannibal on the payroll. Despite some Rob Zombie commonalities, its moral maneuverings are fascinating and the best kind of complex. It’s Demme’s hallmark clashing of worlds again, but this time the outcast is way out: Hannibal the Cannibal Lecter. Demme’s task then becomes more difficult, bringing this psychopath into the fold. In order to make Lecter seem more likeable, Demme diverts misgivings to another character: Dr. Chilton.

I’ve seen and taken part in this psychology before. It’s a strategy my family employs: Find someone worse. We get along best when we’re sharing in each other’s irritation about an unhelpful waitress or political pundit. We forge a bond through the mutual understanding that there is someone worse out there, and that we agree on who that is. Demme gets that and uses Chilton to draw focus away from the much more objectively nefarious Lecter.

I want to jump to Lambs’ final scene where a newly free Lecter checks in with Clarice over the phone. After congratulating her and expressing some admiration, he jokes about a having an old friend over for dinner. The viewer, maybe Clarice too, knows this means that Lecter has hunted down Dr. Chilton—his former warden, played by Anthony Heald—to some unnamed tropical island and plans on killing him and eating him. Lecter hangs up, the music swells seriously, and the shot cranes up to give some sense of resolution. Yet, a killer—not the killer, at least of this movie, but a known serial killer—has not only gotten away but also promised more blood. Yet, the movie doesn’t care much about that. Why not? Why don’t I?

The short answer is that I like Lecter and I don’t like Chilton. The longer answer is that the movie has set up deeply relative moral terms that subvert a conventional code of movie morality. The code it introduces is twisted, no doubt about it. But director Jonathan Demme is reckoning with it from the moment Clarice enters FBI headquarters. The first 15 minutes are spent introducing Hannibal Lecter and Dr. Chilton but in playful ways.

Chilton first enters by finishing a sentence that begins with Clarice talking to somebody else, Jack Crawford, about Lecter. Demme makes use of one of my favorite unnecessarily savvy cuts.

CRAWFORD: Do your job, Starling. But never forget what he is.

STARLING: And what is that?

(Cut to CHILTON’s office, CHILTON in a chair)

CHILTON: Oh, he’s a monster. Pure psychopath. So rare to capture one alive.

I suppose this choice is made to be formally clever, but I also think it evokes Lecter’s mystery. These suits hype him before he arrives, piquing interest. This editing also draws a through line between Crawford and Chilton’s thinking. They both represent the establishment, someone trustworthy in a different movie, someone pathetic in this one.

He begins by hitting on Clarice, inviting her out to see the Baltimore nightlife and offering to be her guide. His slicked back hair and glistening teeth, though, imply plans a little more untoward than an Orioles game and a digestif. Demme pauses to highlight Chilton’s eeliness.

He begins by hitting on Clarice, inviting her out to see the Baltimore nightlife and offering to be her guide. His slicked back hair and glistening teeth, though, imply plans a little more untoward than an Orioles game and a digestif. Demme pauses to highlight Chilton’s eeliness.

Upon Clarice’s rebuff, his tone switches from flirtatious to business-like. “Let’s make this quick then,” he says, tapping a security card on the table. This seriousness works as a front whereby he begins to demean Clarice. While walking, Chilton flippantly suggests that Crawford selected her because she was a woman and could therefore titillate Lecter. This culminates in his pun about her being Lecter’s taste. It’s a real groaner, and Heald’s delivery belies any tact.

But then the debasing turns into a kind of terrorism. By then, they have entered the guts of the institution, somewhere underground. There, Demme turns on the red lights and ramps up the grumbling score. Chilton, his face aglow in demonic red, describes the procedures to Clarice. He then gives her a warning by showing her a picture—which he keeps on him at all times?—of what happened to the last woman who didn't take his protocols seriously.  We never see the photo, but Chilton seems impressed by it, smirking at the factoid that Lecter’s pulse never got about 85. So, even though Lecter ought to feel culpable, Chilton becomes a proxy recipient of Clarice’s unease. This turn from flirt to jerk to menace reads like the textbook tracking of harassment.

We never see the photo, but Chilton seems impressed by it, smirking at the factoid that Lecter’s pulse never got about 85. So, even though Lecter ought to feel culpable, Chilton becomes a proxy recipient of Clarice’s unease. This turn from flirt to jerk to menace reads like the textbook tracking of harassment.

Lecter, though, engages with Clarice in an opposite trajectory from Chilton. Lecter’s opening gambit is adversarial, like when he asks her if she’s seen this classic Italian vista that he knows by memory. He intuits she’s never been, but her answer will give him personal fodder to exploit. When she holds her own, he grows more curious—“That’s very slippery of you, Agent Starling” he says, bested for a moment. This exchange, like profiling ping pong, anchors the movie throughout. This first meeting though is perhaps the most famous because it the first time we let our guard down with Lecter. In particular, I feel won over by a particular moment, after Clarice forces a topic change, where Lecter becomes transparent, meta even: “No, no, no. You were doing fine. You had been courteous and receptive to courtesy. You had established trust with the embarrassing truth about Miggs, and now this ham-handed segue into your questionnaire. (He tuts, three times.) It won't do.”

Some may read this as manipulative or outright mansplaining. I read it as motivational. Lecter continually prods Clarice into exploration, and this first scene sets that tone. Yes, Lecter will eventually gain, though indirectly, from this relationship, but his guidance is not only about the case. It’s also about her wounded psyche, which he empathizes with. Roger Ebert, in his 2001 revisiting of this movie, explains what these two have in common:

“They share so much. Both are ostracized by the worlds they want to inhabit—Lecter, by the human race because he is a serial killer and a cannibal, and Clarice, by the law enforcement profession because she is a woman. Both feel powerless—Lecter because he is locked in a maximum-security prison (and bound and gagged like King Kong when he is moved), and Clarice because she is surrounded by men who tower over her and fondle her with their eyes.”

Fueled by ambition and curiosity, Clarice trusts Lecter and looks for ways to circumvent Chilton. The audience follows suit. This is the inversion of the moral order of the movie, and it raises an interesting question about how morality works in pieces of fiction, inviting the notion of relativism. The assumption with most realistic texts is that viewers would take their presumably well-defined moral code from actual life and project it onto the dream of the movie. This code would probably include the notion that killing is worse than being a shitheel. With this movie, I am manipulated into forgetting or ignoring that.

A lot of this inversion has to do with what is shown. Lecter commits some gruesome murders in this movie, but much is not shown, and what is shown is aesthetically controlled. His escape plan is elegant, soundtracked by classical music and foregrounded with his thoughtful drawings. Even when he flays the guard, the violence carries a metaphor of escape and transformation, not unlike Buffalo Bill, our other killer.

A lot of this inversion has to do with what is shown. Lecter commits some gruesome murders in this movie, but much is not shown, and what is shown is aesthetically controlled. His escape plan is elegant, soundtracked by classical music and foregrounded with his thoughtful drawings. Even when he flays the guard, the violence carries a metaphor of escape and transformation, not unlike Buffalo Bill, our other killer.

Soon after escaping, Lecter kills the ambulance workers and several people at the airport, but we learn this second hand and the effect dissipates quickly because we don’t see him do it. Without any emphasis, these deaths work to explain Lecter’s cunning and make his freedom seem ingenious, earned.

What’s more is that not once do I fear for Clarice. Nor does she fear for herself. “He would find that rude,” she says, when asked if she thinks he’ll come after her. During the movie, this makes sense, and I think it puts the audience at ease, even if it shouldn’t. The viewer’s empathy and experience has been so tied up with Clarice that they (want to) feel the same as she does. If she’s not worried, why should they be? It’s a matter of creating closeness with the main character. But how?

It’s three pronged. Jodie Foster portrays her as determined but vulnerable—the engrossing funeral home and autopsy scenes do much of that work. Then there’s Ted Tally’s screenplay and Thomas Harris’ novel. Both of these build the plot around her ability to navigate her surroundings, which are largely masculine and foreboding. And perhaps most of all, Demme employs subtle methods that reel in audiences. He films two-shots (shots where two characters are talking) with what he calls a subjective camera. He places the camera directly between the actors, so when somebody is talking, they are looking directly into the camera, allowing the viewer to see what Starling would. When Starling talks, it’s less directly into the camera. This choice aligns perspectives with Clarice.

The movie gives none of the same opportunities for depth with Dr. Chilton. He emerges from the school of thought that says he gets a defining characteristic and then all lines funnel into that understanding. His characteristic is self-absorption, and Anthony Heald leans in. When Clarice returns to Lecter without including Chilton, he rants—in telegraphing exposition—“What you are doing, Miss Starling is coming into my hospital to conduct an interview, and refusing to share information with me, for the third time,” and then, weakly, “I have rights.” His attention is focused on being left out, not the case. This weakness leads to desperate acts.

Chilton surveils a private conversation and then later intimidates Lecter into some information, all of which he parlays into attention for himself. After bringing his chattel to Tennessee, he pimps himself to the newspapers and promotes himself once more. I’m sure I would like him more if I saw him feeding his goldfish or struggling to connect with his father, but that is not his purpose.

He’s only in a handful of scenes, maybe ten minutes, but Lambs is the movie where Hopkin’s 17 or so minutes was worthy of a male lead actor, indicating that screen time and impact on the movie are not the same. Chilton’s presence need only orbit the movie because Heald understands he cannot operate like a major character. In an interview with the A.V. Club, he discusses how Demme saw his face as a kind of shorthand for the role:

“It’s a sad fact that screen time is very expensive, and any way that the producer can limit inessential screen time in terms of setting up the story or establishing the characters, it’s to their benefit. So if they can they cast a secondary role with somebody who, the minute the audience sees them on the screen, they already have an established series of responses that are built in. So that the producer doesn’t have to spend a lot of time establishing that I’m a nasty guy, that I’m a sleaze-bucket, that I’m a weasel.”

Heald has made a comfortable living off his particular charm or lack thereof. But it seems to have hemmed him in a bit too. There was plenty of opportunities after Lambs—mostly Boston Public or Boston Legal—but several others roles that I can recall feel like retreads of his Chilton character. There’s an X-men movie where he terrorizes mutants; there is the forgotten chestnut Bushwhacked where he plays the beautifully named character Reinhart Bragdon who is so slimy that we root for the normally irritating Daniel Stern; and there is an episode of Frasier, where Heald and Kelsey Grammar quibble over wine club protocol, called “Whine Club.” (Now that I think about it, Dr. Chilton seems like he could easily share a tailor or personal shopper with Frasier Crane.)

Heald has made a comfortable living off his particular charm or lack thereof. But it seems to have hemmed him in a bit too. There was plenty of opportunities after Lambs—mostly Boston Public or Boston Legal—but several others roles that I can recall feel like retreads of his Chilton character. There’s an X-men movie where he terrorizes mutants; there is the forgotten chestnut Bushwhacked where he plays the beautifully named character Reinhart Bragdon who is so slimy that we root for the normally irritating Daniel Stern; and there is an episode of Frasier, where Heald and Kelsey Grammar quibble over wine club protocol, called “Whine Club.” (Now that I think about it, Dr. Chilton seems like he could easily share a tailor or personal shopper with Frasier Crane.)

Returning to the end: There was some debate about how to show and how much to show of Lecter’s assault on Chilton. The book has Chilton ready for vivisection in his office; Tally’s screenplay included a similar fate, although this time somewhere in Chesapeake Bay. Both of these show Chilton captured. Torture is imminent. Demme seems to have fought them on the darkness of that final image. In a Deadline 25th Anniversary revisit, Tally recalls the conversation, here voicing the director’s concerns:

“‘You know, that’s kind of icky. Chilton is despicable, and we don’t like him, and he’s a crumb-bum, but he’s still a human being, and to have him trussed up for slaughter just is too squirmy. Ted, shouldn’t we give him some kind of fighting chance?’”

And that seems like the correct impulse, if the movie wants to continue to mess with the moral order. Any undue suffering could tip the movie over into something either mean-spirited or unbelievable. That problem belongs to a host of lesser movies, including Lambs sequel Hannibal, a movie that revisited all of Lambs dark energy but none of its complexity. With no Chilton, Clarice has little to push against, Lecter defaults into the villain role, and interesting short-circuiting of morality is eliminated in favor of what amounts to blood-soaked victory lap for a fan favorite character. But not with Lambs. Demme saw his key characters as more complicated and deserving of depth than that. All except Chilton. He is the sacrifice.

Lewis DeJong lives in Tucson, Arizona where he is a Lecturer at the University of Arizona. His work (fiction, essays, otherwise) has appeared in North American Review, Sonora Review, Rabbit Catastrophe Review, and others. He keeps a Buffalo Bill glossy photo (pictured) in his front window to keep solicitors away from his home, which he shares with his cat Trudy.

Lewis DeJong lives in Tucson, Arizona where he is a Lecturer at the University of Arizona. His work (fiction, essays, otherwise) has appeared in North American Review, Sonora Review, Rabbit Catastrophe Review, and others. He keeps a Buffalo Bill glossy photo (pictured) in his front window to keep solicitors away from his home, which he shares with his cat Trudy.

~