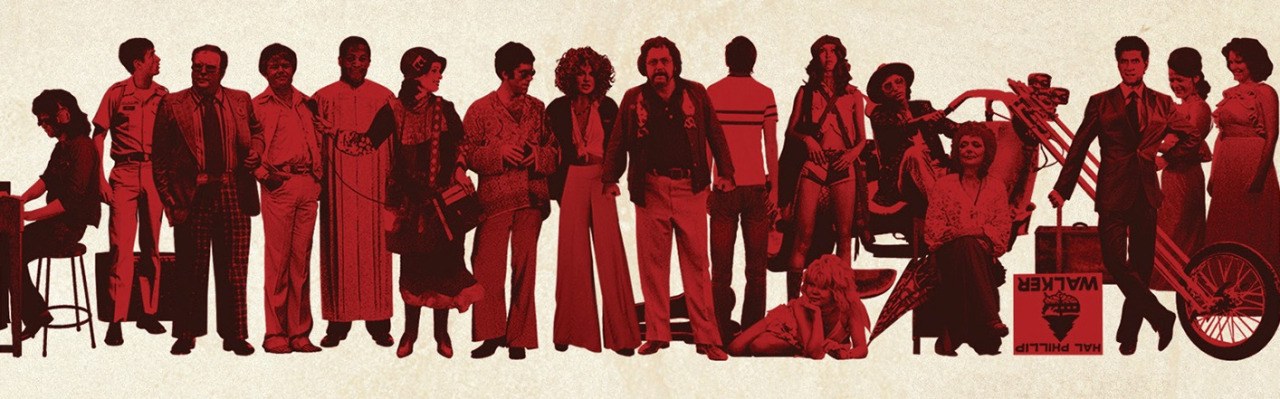

Barbara Harris as

Albuquerque in

Nashville (1975)

by Adam al-Sirgany

Everybody’s a sideman in Nashville. A legendary starlet entrapped in her room, backup singers, and bedroom singers, a disaffected young man and a soldier on a hopeless mission. Frog, the long-haired studio pianist, who is disappointingly not Pig; political lackeys; a salesman with a dying wife who can’t get his niece to see her. Cuckolded husbands and husbands who’d like to be cheating, women carving notches in a famed folk singer’s bedpost… In ways that could only be managed in a country-city like Nashville, their stories intersect and dissipate and an aspect of community, with its frustration and humor and banality, skitters through.

Everybody’s a sideman in Nashville. A legendary starlet entrapped in her room, backup singers, and bedroom singers, a disaffected young man and a soldier on a hopeless mission. Frog, the long-haired studio pianist, who is disappointingly not Pig; political lackeys; a salesman with a dying wife who can’t get his niece to see her. Cuckolded husbands and husbands who’d like to be cheating, women carving notches in a famed folk singer’s bedpost… In ways that could only be managed in a country-city like Nashville, their stories intersect and dissipate and an aspect of community, with its frustration and humor and banality, skitters through.

Often genred comedy, sometimes political drama, Altman called Nashville a musical, and it holds all these modes, an assemblage of the old verities against the backdrop of a small city in the summer of a presidential election.

The film begins with an extravagance of self-referentiality: a commercial, less trailer than elaborate credit roll mimicking ads for the Grand Ole Opry. All your favorite stars in Nashville! This list is long—twenty-four actors—and to see it in 2017 is to encounter a certain prescience. The likes of Lily Tomlin (her first film), Ned Beatty (post-Deliverance but just three years into his career), Jeff Goldblum (his third film and one of his first major roles), Karen Black (whose second sister status here presages her post-Nashville career), Shelley Duvall (a rising star but prior to her performances in Annie Hall, 3 Women, The Shining).

Released in June of 1975, Nashville took its primary writer Joan Tewkesbury several months of 1973 and ‘74 to research and to write, and the shooting (of the film) happened over two months (in August and September) of 1974. Other limitations to production and release notwithstanding, Nashville was among the first major studio projects after the close of the Sixties and Nixon’s retirement from the White House—not to mention during the drawdown of the American occupation of Vietnam and the draw-up of the 1976 election cycle and American Bicentennial celebrations, to respond to their immediate happenings. It remains an apt portrait of the horrors and the glories of that time. Artistically, personally, for sheer curiosity, I regret not having lived through those hawk and dove days whose legacy has been as much their hope as their social brutality.

~

One classic reading of the film’s basic trajectory goes something like this: Over the course of five days, in the lead up to a presidential primary, Replacement Party candidate Hal Phillip Walker’s people organize a variety of country and folk singers, famed and unheard of, to perform a public benefit in support of Walker (who is never seen on camera but is voiced, by Thomas Hal Phillips). That event comes together by no small miracle of vice and salesmanship, and begins with the appearance of its headliner, the frail thus immaculate Barbara Jean (Ronee Blakley).

Barbara Jean’s innocence is striking. At times diffident, at times unabashed in ways that speak as much of mental wards as kindergarten classrooms, she has only come to perform at the Walker event after her manager-husband (Allen Garfield) pulled her from stage the day before for drifting into a rambling anecdote about her grandfather. Barnett, her husband, reluctantly agrees to the Walker appearance as a means to appease the disappointed crowd.

Barbara Jean’s innocence is striking. At times diffident, at times unabashed in ways that speak as much of mental wards as kindergarten classrooms, she has only come to perform at the Walker event after her manager-husband (Allen Garfield) pulled her from stage the day before for drifting into a rambling anecdote about her grandfather. Barnett, her husband, reluctantly agrees to the Walker appearance as a means to appease the disappointed crowd.

So it happens by accident of her overburdened purity that Barbara Jean stands in her white dress in front of a massive American flag, on the steps of Nashville’s Parthenon, Walker’s Replacement Party banner behind her, and she is finishing her first marvelous song about family—I still love mama and daddy best, and my Idaho home—when she is shot, probably dead.

~

Like Mellencamp, I was born in a small town—which isn’t the whole story but might account for certain matters of taste and my ways of experience and being. Six hundred miles from Nashville, it was a small town of two thousand in farm country in the rural Midwest, where corn is grown and where Kraft cheese was first branded. Folks there were folks. People wore plaid before it was hip. They listened to country music from childhood and watched Lawrence Welk when they got too old for road drinking.

As her parents did, my mother grew up there. She lived through the best known years of the Sixties as a college student, travelled Europe then America, lived in a small city, and quietly returned to this small town to farm with her parents and marry late and unlikely to an Egyptian jeweler. She kept a fine collection of records—Simon and Garfunkel, Diana Ross, Carole King. She was a school teacher then elementary school principal and superintendent and by these virtues a minor celebrity. Even in that small town milieu, where anyone may speak with anyone about politics or a new paint job or the sexual sins of her husband without much surprise or shame, my mother was stopped often in the grocery store and in restaurants, it was not uncommon for folks to wave us into parking at the edge of a bean field just to talk predictions for an upcoming high school football game.

This way of encounter may be quaint, it is certainly provincial. Often it produces moments of that boondocks eeriness or dime-store wisdom, which so fascinate cosmopolitan people who in passing through are charmed and frightened and pathetically bored in turns. But it is not a simple way of being. On the contrary, it demands many interactions of consequence and the acknowledgement of many other people.

And it is that acknowledgement, wherever we are or are from, by which the human condition is substantiated. As says Hannah Arendt, who describes herself not as philosopher or theorist but storyteller, “No life, not even the life of the hermit in nature’s wilderness, is possible without a world which directly or indirectly testifies to other beings…. All human activities are conditioned by the fact that men live together, but it is only action that cannot be imagined outside the society of men.”

~

Every day I choose to frame an Odyssean tale of myself as a country boy encountering the great cities of the world, yet I’ve only just begun to think of Ithaca. My adult years have taken me to cities, trending increasingly urban—Galesburg, DC, St. Louis, Tucson, Cairo, Philly, New York—to study politics and writing, sometimes the two together. I can quote whole passages from forgotten speechwriters and theorists of natural law. I have shared the stage with Pulitzer Prize winners who wouldn’t remember my name, and have campaigned for candidates as hobby and as profession—not a one of them has won. On the night Sisi was elected President of Egypt, I stood with the crowd outside his palace, while firework ash burned through flags above my head, and last November, on American Election Day, I was urging folks to their polling places, followed by a cop at a distance of two blocks and a group of nine-year olds shouting, “Faggot,” steps behind me.

I lose sleep every week to a vague but potent thought that something tangible—something made or published, something changed or understood—may have come from time already gone, if for all my opportunity I would have planned. But I’ve followed instead content preceding form, an aimless nature. I have collected notebooks full of poems about characters met while busking and quotations from writers I admire. My employment history is sporadic. I once removed a comma from a policy recommendation, and that policy became Federal law, so that what isn’t there is precisely what I can claim that I have written.

~

My impulse is to blame my worries about the direction of politics toward social aggression, about my own undirected drift and insignificance, on the bureaucracy of cities, the bustle and run and unnecessary hierarchies that dehumanize the individual in a mass of culture, but I suspect the truth, if there is one, has as much to do with a disconnection from place and with a resistance to and pursuit of narrating what I expect is expected of me: an idea of a single protagonist on a hero’s journey, or toward a hero’s tragedy, what Campbell calls the monomyth, “a magnification of the formula represented in the rites of passage: separation—initiation—return.”

Two years ago, the writers Ryan Grandick and Manuel Muñoz introduced me to Nashville in a workshop Muñoz was holding in Tucson, Arizona. Sections from a novella-in-vignettes I’d drafted were being considered by the class and something of my work’s recursiveness and accumulation, its interest in political discourse and its disinterest in a singular Odysseus led both men to offer emphatic notes to see Altman. I would avoid the film for two years and three dozen drafts and finally lie down to watch it after what I stubbornly decided would be a real last revision of that work landed me in bed with an illness of minor exhaustion.

Perhaps because I grew up in a community in which I could be alone but I could not hide, I came to believe in an America of democratic discourse built from the discordance of differing opinions and from the real and familial affection developed with those we spar with time and again. I was, for example, always aware that I was an Arab-American in a conservative community after September 11th, 2001, but I have only learned since leaving home to feel unsafe there or anywhere else—much like a childhood friend from that same community who once explained to me that he realized only after moving to LA that the word faggot didn’t always have our implied before it and that he now struggles to tell when it’s there.

This education, like all education, has been a difficult one, and much of my writing, my novella included, has been in response to it. In my late teen years and early twenties, I lived in and out of DC and traveled there frequently. It was in Washington I learned many of my possible identities and that I might politicize them, that others could if I didn’t, could if I did. That troubled me as a young person still capable of idealism and knowing there was much to be seen. In the years that followed, I found thinkers and characters to help me understand what these conditions meant. There were many characters to find, and they bumped at odd angles, and each and every one was equal and well-meaning, at least to me.

Of course, a person is not a character, and the closer a character comes to the mythic, the more that character is a representative—of what one hopes to be or to avoid or to in some way fulfill—which is Campbell’s psychoanalytical point. The months, the five years, preceding my first watching of Nashville were an immersion in worlds of social propaganda, real and fictive, two graduate programs in creative writing followed by a job fundraising for PACs before a presidential election. And the outcomes of that time—my failures to say what I had intended, to answer the questions I had asked; my failures to persuade, even myself; my determination to perpetuate spaces where there were no villains, which seemed, by those efforts, only to draft cartoon renditions of hate on all sides—left me pinned to my bed with a shameless ennui, a refusal to partake in anything.

One scene from Nashville is evocative of this time for me. It is shot in a bar where, among many other goings-on, Jack Triplet (Michael Murphy) is busily gathering promises that singers will appear at an event for Hal Phillip Walker—Walker, that proper but grotesque hero of this tale, that John-Henry-esque everyman who fights the machine, and yet who is absent and so speaks without body or face, speaks through megaphones and proxies, among whom Jack Triplet is the chief. The camera carries between characters, so that, though we have his body, even Triplet is not heard in full and his comments must be inferred.

Lady Pearl (Barbara Baxley) is the manager and companion of singer Haven Hamilton (Henry Gibson), and she explains to Triplet that she never lets Haven get involved in politics, and slips into a drunk and melancholy reflection that is broken up by the camera pan and so must be longer than what is seen:

…you understand we give contributions to everybody. And they are not puny contributions. Only time I ever went hog-wild around the bend was for the Kennedy boys. But they were different…

And all I remember the next few days was I was just lookin' at that TV set and seein' it all, seein' that great fat-bellied sheriff sayin', "Ruby, you son of a bitch. " And Oswald and her in her little pink suit…

And then comes Bobby. Oh, I worked for him… I worked all over the country. I worked out in California, out in Stockton. Bobby came here and spoke. He went down to Memphis, and then he even went out to Stockton, California and spoke off the Santa Fe train at the old Santa Fe depot. Oh, he was a beautiful man. He was not much like John, you know. He was more puny-like. But all the time I was workin' for him, I was just so scared. Inside, you know? Just scared…

~

This fear has no purpose but to reduce one to an impractical inaction, a stasis of discontentment in which I have never wanted to rest, a hopeless stasis identified by the philosopher Richard Rorty as beginning culturally in the American mid-Sixties and developing into his own present moment. Put, as he admits, somewhat too completely, he argues that "[t]he difference between early twentieth-century leftist intellectuals and their contemporary counterparts is the difference between agents and spectators." Insofar as this feels so to my own experience—and it feels so generally—a Nietzschean question presents itself to me: What do we do when our heroes are dead, if we, ourselves are not real heroes, if despite this, we are designed, constitutionally, to require them?

The best answer I can present is a determination to seek some new, more satisfactory rendition that serves our—my—ancient desire, to find a hero for an age that knows too much of its own despair. I don’t have a precise criteria for who that hero might be, but I’d like to submit one character for consideration.

Barbara Harris (Winifred, aka Albuquerque) has had a major Broadway and occasional film career but has never left an impression on the public consciousness quite like, say, Shelley Duvall and her tortured screams as she’s stalked into a bathroom by ax-wielding, “Here’s Johnny” Jack Nicholson. In Nashville’s litany of characters, Harris is easy enough to miss, but she will give a remarkable performance of one of the least remarkable people in Nashville/Nashville.

Albuquerque first appears several scenes into the film. Visually and chronologically, she and her husband Star (Bert Remsen) are among the least of significant characters. In this scene a string of cars hurries away from the Nashville Airport. Shortly before, a crowd had gathered there to attend the welcome home of Barbara Jean, who’d been convalescing in Baltimore from unspecified burns. In the rush from her appearance, a canoe falls from one of the cars, causing a pileup along the highway and trapping nearly all the film’s major characters.

This is the sort of bustling mess Altman loves. As with the bar scene from Carver’s “Vitamins” (Shortcuts, 1993), as with the funeral of Captain “Painless Pole” Waldowski (M*A*S*H, 1970), as with the slough of hospital rooms, bars and concerts that are the featured settings of Nashville, the pileup allows Altman to examine many characters, featured and not, reacting to a single incident as they go on living their lives in the context of his plot: Singer Haven Hamilton argues with his companion, Lady Pearl, about the lyrics of a hit song. A popsicle truck has a boon. Linnea Reese (Lily Tomlin) reveals to Opal from the BBC (Geraldine Chaplin) that she hasn’t taught her children to sing because they were both born deaf, and that it isn’t so that this is awful. Shirtless men in cut-off jeans lean on a car to flirt with girls. Opal emerges again, inviting herself into the tour bus of Tommy Brown (Timothy Brown), a Black country singer bemused by Opal’s oddly self-congratulatory racism.

When Albuquerque is presented she is en medias res of what seems regardless to have been an incoherently told story about a man who made a million dollars on flyswatters with red dots on them and the Industrial Revolution. She speaks in an accent neither quite Southwestern nor Nashville-southern. Her bright yellow top crosses under her shoulders and always looks about to fall, as her restless hair is always falling, and bobbing up again, done as it seems to have been with curlers of greater diameter than her hair is long.

Apart from a peculiar beauty—some daydreamed lovechild of Dolly Parton and Janis Joplin—that the camera views her face-on in this moment may be the only indication Albuquerque is part of a larger plot. So when the talk with her husband falls to bickering—I have a gold record. It needs to be signed.—I fall into what I often fall into when watching quirky characters on screen: I am lulled into their pure comic relief, that mindless opiate of whatever Rob Schneider is in any film where Adam Sandler is the star.

~

I’m not looking to dismiss Schneider or Sandler, or Joseph Campbell for that matter. What I mean to say is that the presence of light characters, even or especially in light or conventionally orchestrated works, speaks to a tradition of conventional individualism, that is, individualism leveled to flatness by each hero’s inability to engage his or her community as a plurality of substantiated others. In a classical hero’s tale, the journeying hero needs dangers to overcome and unheroic others to impress his greatness upon by the acts of his overcoming. To be a hero then assumes that the impression you make on others is significant, that their ability to be impressed is meaningful, that they needed you to do anything at all.

But what if a hero didn’t impose greatness on us, but mingled in our company? I’m thinking of something like Arendt’s premises about active versus contemplative lives: that we exist and are free only as part of communities and only so when we engage in considered acts of speech within them. Says Arendt:

All human activities are conditioned by the fact of human plurality, that not One man, but men in the plural inhabit the earth and in one way or another live together. But only action and speech relate specifically to this fact that to live always means to live among men, among those who are my equals. Hence, when I insert myself into the world, it is a world where others are already present. Action and speech are closely related because the primordial and specifically human act must always also answer the question asked of every newcomer: “Who are you?” The discloser of “who somebody is” is implicit in the fact that speechless action somehow does not exist, or if it exists [it] is irrelevant; without speech, action loses the actor, and the doer of deeds is possible only to the extent that he is at the same time the speaker of words, who identifies himself as the actor and announces what he is doing, what he has done, or what he intends to do…. Still, though unknown to the person, action is intensely personal. Action, without a name, a “who” attached to it, is meaningless…

As one fascinated with the human condition and the relationships of politics and violence to it, as a musician and a writer first engaged by language as a music in itself, I see in Nashville questions I would ask myself. To watch Nashville is, to me, to feel in conversation with its many voices, to be spoken to and so to be again in a place I’ve rarely felt on the ground of my gadabout adulthood, looking, as I have, for communities in my mind. I feel, again, in a place of home, or at least I see its shore.

For Arendt, I think, and for me, to act and to speak are most possible in communities where, as in a proper home, by participating, we are guaranteed a place. Where we ask “who are you” of each other. Altman, often, but especially in a work like Nashville, is demonstrating something like the type of spaces these communities provide, and Harris’ Albuquerque is expressing to those of us contained by private lives something like what it is to be, however tenuously in them, among free equals.

~

Albuquerque by way of Harris, Altman, Tewkesbury manages this without a great deal of time on screen and with few, if memorable, statements. Apart from her final musical number, she speaks a little over 200 words, most of them dubious and/or non-sequitur.

After huffing away from her husband’s pickup, Albuquerque is seen walking along in a high-heeled, knees-together slump, levering herself over the concrete guardrail of a nearby embankment. When she appears again, she has paired up with Kenny Fraiser (David Hayward), whose car has overheated in the fray and who, it will later be revealed, keeps a pistol in his violin case with which he’ll shoot Barbara Jean.

After huffing away from her husband’s pickup, Albuquerque is seen walking along in a high-heeled, knees-together slump, levering herself over the concrete guardrail of a nearby embankment. When she appears again, she has paired up with Kenny Fraiser (David Hayward), whose car has overheated in the fray and who, it will later be revealed, keeps a pistol in his violin case with which he’ll shoot Barbara Jean.

Here is a loose transcription of that dialogue. While brief, it is telling of both Kenny’s incapability to consider other individuals seriously and of Albuquerque’s emotional complexity.

KENNY

What do you do?

ALBUQUERQUE

Well, I know it sounds arrogant, but I'm on my way to town—if I ever make it—to become a country-western singer, or star.

KENNY

Yeah? What are you gonna do if you don't?

ALBUQUERQUE

If I don't. I don't kn- Oh, I could always go into sales.

KENNY

Like ladies' clothes?

ALBUQUERQUE

No. I don't know. Well, I know all about trucks, so I'd go into trucking, I guess.

KENNY

You're kidding me.

ALBUQUERQUE

No, I'm not kiddin' you. I'm in a truck enough. And I know how to fix motors and all that.

KENNY

Nobody'd buy trucks from a girl.

ALBUQUERQUE

I been fixin' motors a long time. They'd buy 'em from me 'cause I know all about motors. Why’d you say that? See, what's happenin' is, if I can't sell trucks and I can't go-

KENNY

Nobody'd buy a truck from a girl.

ALBUQUERQUE

I knew this was gonna happen. Don't say you saw me.

This conversation ends with Albuquerque running off, purse swinging beside her. Her husband, Star, has pulled up in his truck and asks Kenny if he has seen his wife, “a kind of ordinary-lookin’ woman.”

A while later Star is drinking and listening to yet another singer-hopeful, Sueleen Gay (Gwene Welles) perform a provocative and tone deaf number that will become the pivot of her own Nashville tragedy. Albuquerque will wander into this moment, only to run back out again, shouting “What! You?” and “No!” while Star chases after her demanding she come back.

She won’t be heard saying anything else until the end of the film. But this act of wandering in will define her presence in it. Where a community of musicians is, unabashed, she will choose to be partaking. She will be the second entertainment at a drag race where the roar of mufflers will drown her out. We will encounter her in the audience of the Grand Ole Opry, in the background of a crowd at an outdoor amphitheatre, at a party in a wood nestled in the underbrush, leaning against the stage to hear Barbara Jean sing at a benefit for Hal Phillip Walker.

Yes, Albuquerque is beside the stage when Barbara Jean is shot. Shortly before the gunfire, she is pictured against a platform edge—captivated, starry-eyed—and as she so often does, she disappears into Nashville’s miasma of peoples.

In the aftermath of the shooting, Albuquerque wanders on stage as a shocked and wounded Haven Hamilton refuses the situation. “Y'all take it easy now. This isn't Dallas. It's Nashville.” he declares. “This is Nashville. You show 'em what we're made of. They can't do this to us here in Nashville.” Walked from the stage by Del Reese (Ned Beatty), Haven insists everybody sing. “Somebody sing. Somebody Sing. Somebody sing. Sing. Sing.” he shouts, handing Albuquerque the mic.

Quietly at first, she takes up this call, beginning a song to a tune not incidentally reminiscent of “Dire Wolf” by the Grateful Dead. You may say I ain’t free. It don’t worry me. Her cheeks softly round but pull at her cheekbones and jaw as her mouth moves: pleasant and lovely, yet drawn, almost cartoonish, even by comparison to the curious, long-faced, toothsome southern belles in whom Altman has found his beauties. Albuquerque is no facsimile, and couldn’t be, but a demonstration of her own worthy potential, a disheveled and bird-mouthed pixie tossing roses to the crowd.

This is hardly a moment of uniform joy. There is as little sign of the candidate as ever, only his design, yet his proxy self Jack Triplet insists somebody “Get Walker out of here!” Barbara Jean’s husband Barnett yells that he can’t stop that blood, man. Rushing through dispersing bodies, Opal begs to know what’s happened. Sueleen Gay, ready for her chance—after disillusionment, at last—to sing, with Barbara Jean, leans against a wall with a teary-eyed look of dismay. A young man stares at the stage with a face of doped and open-lipped nothingness. Del Reese pulls his wife off stage, “Come on. I need you.” An old neighbor of Barbara Jean’s troubles his way through the crowd. A nameless woman mouths the hook of the song. A police woman roams the perimeter.

As Arendt says in her work, The Human Condition:

The stature of Homeric Achilles can be understood only if one sees him as ‘the doer of deeds and the speaker of great words.’ In distinction to modern understanding, such words were not considered to be great because they expressed great thoughts… but speech and action were considered to be coeval and coequal, of the same rank and the same kind; and this originally meant not only that most political action, in so far as it remains outside the sphere of violence, is indeed transacted in words, but more fundamentally quite apart from the right words at the right moment, quite apart from the information or communication they may convey, is action. Only sheer violence alone is mute, and for this reason violence alone can never be great.

Think Sherwood Anderson and Garcia Marquez, those tales that by their magic leave us walking known streets glorious, harried. Think of those stories before fairy tales were asked to answer all unease, where Sleeping Beauty is raped back into the world awake. What was the sense of this? What does it mean? And why the hell, anyway, was there a primary for a candidate who invented his own party to run on? Even as I find myself humming along, head bobbing loosely in time, a shock of adrenaline still drugs my blood. Even as I plead for ease, I am certain my answers will be incomplete. And Albuquerque welcomes this, she swells with this tension, offers it to us. She sings.

It will take a few minutes, but before song’s end, the stage will clear of all signs of murder; Barbara Jean’s band and Linnea Reese’s gospel choir and the whole clapping crowd will join in on an imperfect cleansing of the moment that will extend beyond the film, to Jack Kennedy’s shattered cranium, at least. It don’t worry me. It don’t worry me. You may say I ain’t free. It don’t worry me.

It will take a few minutes, but before song’s end, the stage will clear of all signs of murder; Barbara Jean’s band and Linnea Reese’s gospel choir and the whole clapping crowd will join in on an imperfect cleansing of the moment that will extend beyond the film, to Jack Kennedy’s shattered cranium, at least. It don’t worry me. It don’t worry me. You may say I ain’t free. It don’t worry me.

In another sort of film, this reveal of Albuquerque’s talent, of her importance, would be the answer. The support of these people, the means by which she was finally glorified, the proof that her quirk was her genius. What I want to propose about this ending though is that whatever happens next—whether Barbara Jean recovers or survives, whether Walker becomes President, whether or not or temporarily Albuquerque is famed—what makes this character matter is that she has always been real within her own little communities—Altman’s film, these five days in the music scenes of Nashville—that her importance was her presence and not her journey. Long before any inference she held those communities together, she moved within them. She spoke. She wandered amongst and in. And as Nashville made Albuquerque, she made Nashville, too, a little more real and free.

Adam al-Sirgany was raised on a farm outside Stockton, Illinois, in the township of Nora. His careers as a writer and as an actor began simultaneously when he appeared as Daddy in a high school performance of Edward Albee’s The Sandbox, a show for which he wrote an audience introduction. In the twelve years that followed, he attended five colleges and universities. al-Sirgany has only ever voted by mail, and as a consequence his ballot was once awaited as the tiebreaker in a township road commissioner contest. Back home, he is very unpopular with a certain, out-of-work road commissioner.

Adam al-Sirgany was raised on a farm outside Stockton, Illinois, in the township of Nora. His careers as a writer and as an actor began simultaneously when he appeared as Daddy in a high school performance of Edward Albee’s The Sandbox, a show for which he wrote an audience introduction. In the twelve years that followed, he attended five colleges and universities. al-Sirgany has only ever voted by mail, and as a consequence his ballot was once awaited as the tiebreaker in a township road commissioner contest. Back home, he is very unpopular with a certain, out-of-work road commissioner.

~