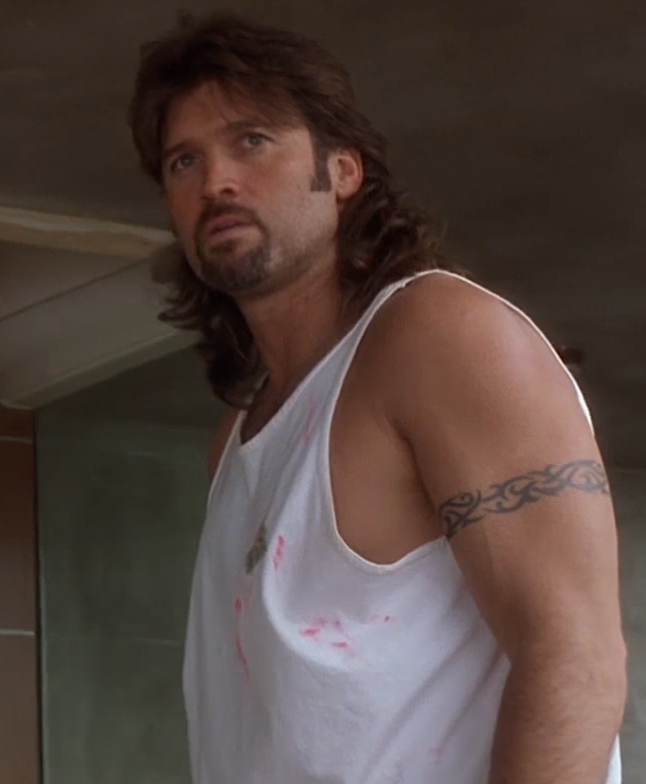

Billy Ray Cyrus as

Gene the Pool Guy in

Mulholland Drive (2001)

by A.A. de Levine

I. The box.

Mulholland Dr., like all of David Lynch’s neo-noirs about people finding trouble in Los Angeles, exists partially within a dream. In this case, the dreamer is Diane Selwyn (Naomi Watts), an actress treading water in Hollywood as her relationship and career aspirations collapse around her. Diane’s dream–a fevered, guilt-studded wish fulfillment–is populated by people from her waking life. She’s Dorothy Gale dreaming of a new self in Betty (also played by Watts), an ingenue swept from her small town to a fantastic kingdom. Betty clues us into what is happening around her right at the beginning of the film: "I just came from Deep River, Ontario,” she says, “and now I'm in this dream place.” A literal dream girl swathed in pastels, Betty is everything the dreamer is not. Diane is bitter; Betty is hopeful. Diane’s career is stagnant; Betty’s innate talent opens doors for her almost immediately. Diane is consumed with jealousy and lust; Betty is innocent, inexperienced. Diane–as we’ll soon see–dreams of revenge and shattered windshields and mullet-wearing pool boys ruining her nemesis’ life.

Mulholland Dr., like all of David Lynch’s neo-noirs about people finding trouble in Los Angeles, exists partially within a dream. In this case, the dreamer is Diane Selwyn (Naomi Watts), an actress treading water in Hollywood as her relationship and career aspirations collapse around her. Diane’s dream–a fevered, guilt-studded wish fulfillment–is populated by people from her waking life. She’s Dorothy Gale dreaming of a new self in Betty (also played by Watts), an ingenue swept from her small town to a fantastic kingdom. Betty clues us into what is happening around her right at the beginning of the film: "I just came from Deep River, Ontario,” she says, “and now I'm in this dream place.” A literal dream girl swathed in pastels, Betty is everything the dreamer is not. Diane is bitter; Betty is hopeful. Diane’s career is stagnant; Betty’s innate talent opens doors for her almost immediately. Diane is consumed with jealousy and lust; Betty is innocent, inexperienced. Diane–as we’ll soon see–dreams of revenge and shattered windshields and mullet-wearing pool boys ruining her nemesis’ life.

The film’s plot, while split between a dream and a living nightmare, is straightforward: Diane’s girlfriend, Camilla (Laura Harring), has outgrown her, casting Diane aside in favor of a relationship with her director, Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux). Camilla neither wants nor needs Diane, an obsessive never-was with nothing to offer. And so, as Diane sleeps, she recasts Camilla as Rita, an amnesiac accident victim totally dependent on Betty, a beautiful blank whose new name is plucked from a poster of Rita Hayworth. So much of Diane’s dream world is built on movies, melodramas, and crime capers synthesizing into her masterpiece. In her dream, Adam Kesher plays himself but worse, hapless and impotent. Shadowy mobsters have seized control of his latest movie, The Sylvia North Story, forcing him to cast their choice for his film’s female lead. Kesher lashes out, smashing the mobster’s windshield before returning to his home high above Los Angeles. There, he finds his wife in their bedroom, carrying on an affair with Gene Clean the pool guy, played by–who else?–Billy Ray Cyrus.

As Diane dreams herself a new world, drawing on porn and pulp and soapy melodrama, I find myself wondering: from where does Diane conjure Gene? He has no obvious parallel in her waking life, just some pop culture detritus floating with the tides of Diane Selwyn’s subconscious. In her dream, Gene exists primarily as a mechanism to punish Adam, to diminish him, to loom over him both in stature and in moral fortitude, a working class man in tight jeans who will nonetheless get everything to which the all-black designer clothes-wearing artiste believed he was entitled. But he also reveals something playful within Diane’s subconscious: armed with a luscious mullet and a Zen-like calm, Gene isn’t worried about being caught sleeping with another man’s wife in the middle of the afternoon; these things happen. As Mrs. Kesher rails against her husband–that loser, that cuck–Gene gently tells her that, well, “He might be upset.” After Adam manhandles his cheating wife, Gene punches him, calmly informing him that this “ain’t no way to treat your wife, buddy. I don’t care what she’s done.” He’s the Marlboro Man by way of “Margaritaville.” He’s a billboard, a cartoon, a guy she’s seen somewhere, maybe at a far richer person’s house party, maybe from a taxi window, maybe once in a movie.

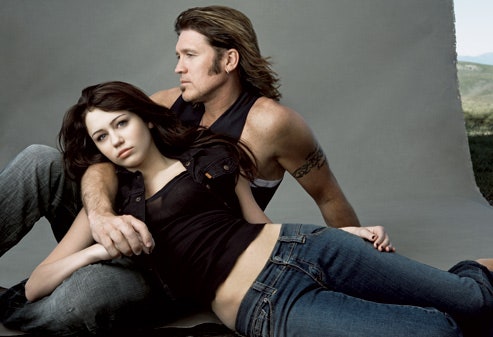

Gene’s mystique–to me, dreaming alongside Diane in my own oddly dark Los Angeles apartment–is inextricable from the fact that he is played by Billy Ray Cyrus, best known for the thoroughly pleasant hunk of bouncy country-pop cheese “Achy Breaky Heart,” and for releasing Miley Cyrus upon the world. On the surface, he seems like an incongruous choice for David Lynch, a director known for delving into the dark surrealism curled and waiting at the heart of the mundane. But Billy Ray is downright Lynchian himself. In fact, he’s as much Lynch’s dream as Diane’s. In 1999, when Mulholland Drive was still a pilot, Cyrus spoke with The Chicago Tribune about the process of bringing Gene to life. “Listen, man,” he recalled the director telling him, “I've watched your tapes, and the way you held that conversation in there with the casting agent, that's the character: Just be yourself, but become everything that's written in there about Gene.” Be yourself as someone else, a dream within a dream. Cyrus, who would have brought Gene back several times if the pilot had made it to series, said the process of playing Gene was easy: "I've been Gene The Poolman all my life.”

Gene’s mystique–to me, dreaming alongside Diane in my own oddly dark Los Angeles apartment–is inextricable from the fact that he is played by Billy Ray Cyrus, best known for the thoroughly pleasant hunk of bouncy country-pop cheese “Achy Breaky Heart,” and for releasing Miley Cyrus upon the world. On the surface, he seems like an incongruous choice for David Lynch, a director known for delving into the dark surrealism curled and waiting at the heart of the mundane. But Billy Ray is downright Lynchian himself. In fact, he’s as much Lynch’s dream as Diane’s. In 1999, when Mulholland Drive was still a pilot, Cyrus spoke with The Chicago Tribune about the process of bringing Gene to life. “Listen, man,” he recalled the director telling him, “I've watched your tapes, and the way you held that conversation in there with the casting agent, that's the character: Just be yourself, but become everything that's written in there about Gene.” Be yourself as someone else, a dream within a dream. Cyrus, who would have brought Gene back several times if the pilot had made it to series, said the process of playing Gene was easy: "I've been Gene The Poolman all my life.”

But things change, of course. People unlock all kinds of boxes. In February 2011, GQ published an interview with Cyrus while the country singer was at a low point. He was getting divorced, at odds with his record company, and watching helplessly as his daughter dutifully performed the “former child star” phase of her career. During his interview, Cyrus searches the past for the source of his anguish and, there, finds Gene. "Were it not for David Lynch,” he told the magazine, “Miley would never have been Hannah Montana.” It is among the most beautiful and sublimely odd sentences ever uttered by a country singer discussing a video of his Disney star child ripping a bong. Of course, Cyrus meant this in a holistic, butterfly effect sort of way: had he never been cast in Lynch’s film, he may not have gotten other acting opportunities which, in turn, afforded his daughter a path into the industry. But Cyrus felt that Gene might not have been “what God had in mind.” In the same GQ interview, Cyrus recalls driving with Miley into Los Angeles, the two passing a sign that read “ADOPT-A-HIGHWAY. ATHEISTS UNITED.” He views this as a literal highway to Hell, a glittering city overtaken by Satan. “Entering this industry,” the sign seems to say to him, “you are now on the highway to darkness...” Cyrus offers a direct line from Lynch to Satan, another art-house auteur often inspired by Los Angeles. In this way, Cyrus isn’t so much like Gene–carefree and meditative, practicing detachment in an employer’s cold, glass cube of a house high on a hill. He’s much, much more like Diane Selwyn–fitfully dreaming of a life where he’s not to blame for walking, clear-eyed, into an industry famous for eating away at people’s souls. Cyrus’ anxieties about his choices echo that of all Los Angeles-based Lynch protagonists, letting their desires consume them and then, warped by guilt, dreaming up a new and blameless life, a movie reel playing out in their minds until, inevitably, reality seeps in. Maybe he, like Diane, glares at the people in his life, near-feral in his resentment. Or maybe Billy Ray Cyrus sleeps peacefully, dreaming of horses running beneath a wide blue Kentucky sky.

It’s compelling, either way, to think about what he looks at when he takes in the contours of his famous life. It’s a life that has afforded him and his children the kind of financial security, opportunity, and access I think about when, like Diane, I’m standing over my coffee in my unwashed robe, thinking about people and opportunities slipping through my fingers. There were writing jobs that didn’t pan out and companies that crumbled, leaving only logo sweatshirts and tote bags and this coffee mug in their wake. There were, clearly, so many shadowy suits deciding behind my back that I was not The Girl. Diane, Billy Ray, and I... It’s not our fault. There are forces so much bigger than we are, spouting cryptic messages way up high in the Hollywood hills. Or, less cryptically, there are literal signs telling us to turn around as we race towards the fortune and fate we thought awaited us.

I think about Diane at her kitchenette window and Billy Ray standing at a marble counter in his Tennessee mansion and me staring at the wall of my kitchen because my kitchen doesn’t have windows, and I think about how we’re all the same, or maybe just three separate dreams someone else is having. We’re all bitter, at our core. We all have to dream up a Betty to assuage our guilt.

~

II. The key.

In Cyrus’ dreams, he still drives into Los Angeles and passes an adopt-a-highway sign sponsored by environmentally-conscious non-believers. He still brings Miley along with him. Only now she never swung in on a wrecking ball. He dreams he’s more like Gene. Uncomplicated. An angel sinning, honest and uncaring.

He dreams of stopping the car at a diner, battling an uneasy feeling as he drinks his coffee, eats some eggs. He feels like he’s been here before, has felt this same crackling electricity and heard this same low drone in a dream. He feels compelled to walk out to the back of the diner, fighting his impulses, telling himself to be a man about it. He walks slowly, the electricity building, the ground swaying beneath his boots. His dread grows as he walks, some dark, liquid thing expanding in his belly. He thinks about how life was so different in Flatwoods, Kentucky, playing baseball and listening to Bluegrass. He thinks about the time he had to live in his car while trying to make it big in Los Angeles, the Devil staring down at him from his house on the hill. He thinks about how much he hates Los Angeles, or how much it hates him. How much he loves it. Or maybe he forgot what he thinks about Los Angeles at this point, because all he can focus on now is the dumpster at the edge of the lot and the dread and the black sludge in his gut and the droning and the fact that, oh God, there it is...

His worst fears, ugly, staring him in the face. His daughter and the Devil, this town and its promises, cars and big houses. And Billy Ray Cyrus’ legs buckle beneath him.

He told his GQ interviewer that he never made a dime off his daughter, but now he has to come face to face with reality in a sun-bleached diner parking lot inside a dream that won’t let him wake up.

Gene doesn’t dream like that. How could he? He’s just a weapon in Diane’s dream, a blunt object battering against Adam Kesher’s head. Maybe Billy Ray Cyrus dreams of Gene too, a steel rod against the glass, breaking down the things he thought he wanted.

III. Behind the diner.

In a 2013 interview with The Hudson Union Society, Cyrus is asked again about working with Lynch. He recalls Lynch taking him aside and telling him that acting is about “taking a moment and making it real.” The director said–probably haltingly, we can imagine, eyes closed and fingers fluttering before his face–that Cyrus could have a real future in acting if he simply kept focusing on that, on making moments real. Cyrus follows this by saying the finished movie was “dark.” Too dark for Cyrus. The experience prompted him to pray to God and ask if he was really meant to pursue a career as an actor.

God answered by sending the script to Doc.

The PAX TV series followed a good Christian doctor from Montana (which is Lynch’s home state, of course, because we’re always in a movie in a dream in a movie) who takes a job in New York City, another renowned den of sin and art and splintered dreams. He strove to remember Lynch’s advice, finding himself struggling on set whenever he forgot to simply make the moment real. Cyrus describes the series as being about “hope and faith and love,” as if in direct contrast to Mulholland Dr., a light on the other side of the dark he’d known.

And this is where I think Cyrus misses the beauty at the core of Mulholland Dr.’s story of loss and pain and ugliness. This is where he misunderstands Gene. Because that film, too, is about hope and faith and love. Specifically, it is about losing sight of these things when we become corrupted by jealousy, by greed, by an ambition that blinds us to our own flaws and shortcomings. In Gene, we find a point of light among all the darkness. We cause pain. We feel pain. We don’t treat our wives that way, I don’t care what she’s done. We can walk away from this glass house, this screaming wife, this long driveway. We can do bad. We can do good. We can wake up.

Cyrus is like Diane Selwyn, but he is also like all of Lynch's Los Angeles protagonists. He is Lost Highway’s Fred Madison, driving straight down a dark road to Hell. He’s Inland Empire’s Sue Blue, too, all Southern twang and flighty uncertainty, always outside of it all, dreaming up a person playing her, a person who’d be able to cast her off in a glittering mansion at the end of the day. In each film, the guilt seeps in. A disheveled woman knocks at the door, telling you someone is in trouble. A man with a camcorder is both at this overwhelmingly beige party your girl dragged you out to and in your house, right now, talking to you on your phone. He knows what you’ve done and what you’re about to do. A smiling man meets you in a hall and you’re confronted with having to destroy him and destroy yourself. You have to wake up. Look at your own guilty face. You have to complete the cycle. You have to know that redemption is earned, not given.

Cyrus is like Diane Selwyn, but he is also like all of Lynch's Los Angeles protagonists. He is Lost Highway’s Fred Madison, driving straight down a dark road to Hell. He’s Inland Empire’s Sue Blue, too, all Southern twang and flighty uncertainty, always outside of it all, dreaming up a person playing her, a person who’d be able to cast her off in a glittering mansion at the end of the day. In each film, the guilt seeps in. A disheveled woman knocks at the door, telling you someone is in trouble. A man with a camcorder is both at this overwhelmingly beige party your girl dragged you out to and in your house, right now, talking to you on your phone. He knows what you’ve done and what you’re about to do. A smiling man meets you in a hall and you’re confronted with having to destroy him and destroy yourself. You have to wake up. Look at your own guilty face. You have to complete the cycle. You have to know that redemption is earned, not given.

There is always something lingering just behind the diner.

None of this affects Gene, of course. He cleans pools. He fucks other men’s pretty wives in glass houses. He wears jeans. He has a mullet. He understands that people get upset. He does not think you should treat your wife like that, buddy. Gene will always be ok. “Just forget you ever saw it,” he tells a flustered Adam Kesher. “It’s better that way.”

For Gene, that’s enough. But for you and me and Diane and Billy Ray, the reality always seeps in. You’re always ending up at the wheel, your daughter beside you, driving down that highway to Hell. You can blame David Lynch and your mom and the Devil and The Industry and your boss and The Man. And you’d be right, maybe. They’re all to blame. But you’re still behind that wheel. She’s still beside you. You’ll still always end up behind that diner, staring yourself in the face.

Hey, pretty girl. Time to wake up.

A.A. de Levine lives in Los Angeles, California. From an early age, de Levine dreamed of becoming a writer. Her first brush with success came in late 2018, when a tweet by de Levine found its way to an Instagram meme account, drawing the attention of at least two former high school classmates. de Levine has previously written for BuzzFeed, Gossamer, and Super Deluxe and has worked as a ghostwriter for an internet-famous robot influencer.

A.A. de Levine lives in Los Angeles, California. From an early age, de Levine dreamed of becoming a writer. Her first brush with success came in late 2018, when a tweet by de Levine found its way to an Instagram meme account, drawing the attention of at least two former high school classmates. de Levine has previously written for BuzzFeed, Gossamer, and Super Deluxe and has worked as a ghostwriter for an internet-famous robot influencer.

~