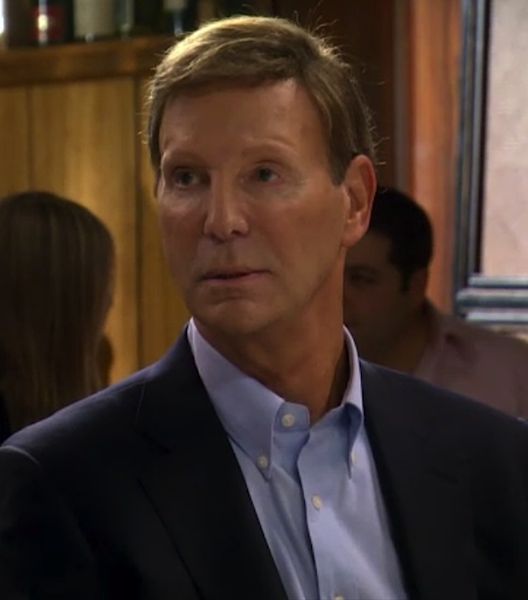

Bob Einstein as

Marty Funkhouser in

Curb Your Enthusiasm (2004-2011)

by Miles Klee

“Who the hell is Marty Funkhouser?” you’d be well justified in asking. “Marty Funkhouser?” It’s that kind of a name: one you’d never forget but can’t quite place. (To me it sounds like a guy you run into at your college reunion and struggle to make small talk with.) He is, to be sure, an essential ancillary of Curb Your Enthusiasm, a bent-reality, improv-based HBO cringe-com that explores the capacity for suffering in a successful, semi-retired man who theoretically has it all. Larry David, co-creator of Seinfeld, sketches the irreverent plots and stars as a fictionalized version of himself, inhabiting a stratum of LA’s affluent west side that skews toward the rich, the Jewish, and the famous. His close friends include Richard Lewis and Ted Danson, who likewise play “themselves,” and many other celebrities have lent their personae to various episodes.

“Who the hell is Marty Funkhouser?” you’d be well justified in asking. “Marty Funkhouser?” It’s that kind of a name: one you’d never forget but can’t quite place. (To me it sounds like a guy you run into at your college reunion and struggle to make small talk with.) He is, to be sure, an essential ancillary of Curb Your Enthusiasm, a bent-reality, improv-based HBO cringe-com that explores the capacity for suffering in a successful, semi-retired man who theoretically has it all. Larry David, co-creator of Seinfeld, sketches the irreverent plots and stars as a fictionalized version of himself, inhabiting a stratum of LA’s affluent west side that skews toward the rich, the Jewish, and the famous. His close friends include Richard Lewis and Ted Danson, who likewise play “themselves,” and many other celebrities have lent their personae to various episodes.

Yet Larry does not behave like a man living in the lap of luxury, with a beautiful wife, entertaining pals, and little to no daily responsibilities. Instead he always plays the victim, chafed by the most basic and mundane civil conventions. He doesn’t see why he can’t use the handicap bathroom stall (if no one else is around) or joke about affirmative action (if he’s not totally racist) or ask a sobbing widow where he can buy the shirt her dead husband is wearing in a framed photo. In short, he refuses to accept that the world does not subscribe to his common sense, which, if it ever functioned correctly, has since been warped by almost unlimited privilege. When he inevitably expresses this dissatisfaction, the world pushes right back. There’s the comedy—at least for me, a man of no material wealth or stature. Because while some find these recurring social suicides hard to endure, I relish them as cathartic, necessary implosions of the self.

Larry’s loved ones abhor this neurotic desire to reverse the flow of the human universe at its molecular level, and they’re often the ones beating him back down as he tries to swim upstream. Occasionally they’ll concede a point, but seemingly just from exhaustion. Into this cast of casual foils walks Marty Funkhouser. He doesn’t show up until the fourth season, yet he’s supposed to be one of Larry’s oldest friends. From the outset, there’s no understanding this. Apart from being middle-aged men who golf at the same country club, they appear to have scant in common. Funkhouser, played by the inhumanly funny Bob Einstein (of “Super Dave Osborne” fame), is a continual irritant to Larry, and is in turn punished for his proximity to Larry. In “The Carpool Lane,” Larry is vexed by a grieving Funkhouser’s refusal to give him a box seat at a sold-out Dodgers game, as it’s “spoken for”—reserved for his recently deceased dad. Funkhouser later has car trouble and needs Larry to drive him to the airport, where he’s promptly arrested in a borrowed jacket full of weed that Larry forgot he’d bought to treat his own dad’s glaucoma.

That volatility and those intimate stakes set the Larry-Funkhouser relationship apart from its clearest antecedent, the endless and venial cold war between Jerry Seinfeld and his down-the-hallway mailman neighbor Newman in Seinfeld. Whereas Seinfeld and Newman were merely petty, their antagonism based more on instinctive prejudice and a cramped New York apartment building than character or ideology, Funkhouser and Larry cause each other the misery inflicted only by our dearest frenemies. Presumably, if they wished, they could mostly avoid each other, as Larry does with countless undesirables in his general orbit. Yet even after the arrest—even after, in “The Ida Funkhouser Roadside Memorial,” Funkhouser realizes Larry has unforgivably filched a bouquet of flowers from his mother’s humble monument in order to resolve a minor marital spat—they bounce back to a cranky sort of status quo. “If you weren’t my best friend, I’d take my bare hands and pop your head off your neck,” Funkhouser snarls in the flower-theft scene, affecting all the gravitas of someone growling more or less the same on The Sopranos. To this, the discomfited yet no less abrasive Larry just mutters to the witnesses, with a bit of a smirk, “He’s not my best friend.” It’s breathtaking. And there is the game of Funkhouser: He’s an overwrought, needy force that for some reason cannot be cut off like a superficial associate. Therefore, the cycle of humiliation and abuse becomes a familiar ritual.

I can’t get enough of their toxic dynamic—it’s unlike anything else on the show. Larry’s younger wife Cheryl (Cheryl Hines) finds his babbling pessimism amusing in moderation. Richard Lewis is so high-strung that Larry can basically never please him anyway, while Ted Danson is too well-adjusted to indulge the bizarre fixation that pulls Larry through a given episode. Larry’s sole true confidant is obviously his Falstaffian, adulterous agent Jeff Greene (Jeff Garlin, playing straight man as co-conspirator), who no doubt suffers greatly on Larry’s account, not least because his wife Susie (Susie Essman, in a shriekingly iconic performance) despises Larry and his schtick. But the friendship is harmonic and justified. The pair enjoys the rapport of men who have talked shit about literally everyone else they know and are barely tolerated by their wider cohort. Larry doesn’t have to worry about alienating Jeff, as there’s technically a contract binding them. Meanwhile, Jeff’s professional perch isn’t so wobbly that he can’t call Larry a fucking moron now and then, but he’ll also easily, lazily defer to his buddy’s needling misanthropy for as long as he can before it blows up in both their faces—as it always does.

Against all this, Funkhouser stands out with an unpredictable valence; he never settles into an archetype. If Larry is waging an uphill battle against minute cultural norms, Funkhouser is his fun(k)house mirror, unequal to the self-appointed, Sisyphean task of molding Larry into a decent guy. Meanwhile, he sort of wants to be him. He goes out of his way to impress Jerry Seinfeld with a bawdy joke during Curb’s fictional reunion of Seinfeld, joyfully announces his divorce not long after Larry becomes sadly resigned to his own, and is basically in sync with Larry’s kvetchy melancholia. At one point, Funkhouser is asked how he’s feeling and murmurs, “Not great,” to which Susie Greene fires back, and not without reason: “Ah, you haven’t felt great a day in your life!” That Funkhouser admits as much, however—refusing to betray his inner truth with the customary “I’m fine, thanks”—puts him squarely in Larry’s mental realm. The Larry of Curb, unlike his habitually deceptive Seinfeld proxy George Costanza, finds himself telling the truth when to do so is tactless or disastrous, if not both. Funkhouser does the same, but his silly forthrightness, as when he tries to pay Larry $50 he owes with a sweaty bill he fishes out of his running shoe, is comparatively innocent, shot through with glum pathos. Curb is largely scored with what must be termed “sad clown music,” and it befits Funkhouser better than it does Larry.

Funkhouser is also (and perhaps most importantly to my particular fanhood) willing to match Larry’s angst on the utterly trivial nonsense that Larry harangues him about. This appears to be the result, intangibly, of Funkhouser’s fundamental happiness as ever at odds with Larry’s eternal defeatism. Sure, he’s moody or even dour at times, but in level spirit he’s convivial and generous—which is how his fights with Larry get started. Among my favorite is when Funkhouser mildly busts Larry’s balls for chiding a doctor who took a lemonade from his fridge without asking. Their back-and-forth about kitchen protocols leads to Funkhouser marking a definitive line in the sand: “Liquids are OK,” he declares, firmly settling his own view, though not the argument. What a delight, then, to see Larry later raid Funkhouser’s fridge of supplies for a massive sandwich, disobeying not just his vividly debated ethics but those of the man whose cold cuts he’s stealing. To Larry, getting away with something trumps the malice of the act, and it’s lovely to see him toss his own code aside in pursuit of instant gratification, but for me the real pleasure is in knowing he’ll be caught, and Funkhouser will have to bawl him out again. It’s akin to when Larry shows the discourtesy of leaving Funkhouser’s 25th anniversary party before dessert, after which I gleefully anticipate Funkhouser’s delayed reaction. “I said, ‘Larry, would you like to make a toast?’” a furious Funkhouser recounts when they see each other again, “and someone said, ‘Larry went home to take a shit’!” He exists to be wounded by thoughtlessness, and his very voice is scraped raw, as if he’s spent decades bellowing himself hoarse at Larry.

Darkening the comic premise of the sandwich, though, is the fact that right when Larry’s making himself a lunch of Funkhouser’s turkey, a far greater evil is being perpetrated against the Funkhouser clan. Larry is at the Funkhouser home with Jeff to visit with Funkhouser’s mentally ill sister Bam Bam (Catherine O’Hara, national acting treasure), who has just been released from institutional care. Jeff impulsively has sex with her while Larry is occupied with the stolen food. In an ensuing dinner scene, Bam Bam dramatically reveals as much with Jeff’s wife Susie present, prompting both men, in a sordid collusion, to propose that she’s riven with novel delusions. Funkhouser, with a great, pained sadness, has her recommitted for this apparent instability. Unlike the illicit sandwich, Funkhouser will not discover this betrayal, and so will not realize how degrading it is for him to forever insist on the honor of Larry and Jeff’s company for eighteen holes at the club. Consider that when Funkhouser, just six episodes later, is given the offer of waived golf course dues, plus gratis parking(!), for snitching on Larry (who has accidentally murdered the club director’s beloved black swan), he doesn’t rat out his “best friend.” Why not? Especially given that a few seasons before, Larry stole a 5 wood from Funkhouser’s father’s open casket, wrongly believing it to be his and placed there by mistake?

The answer, to my mind, is that Funkhouser can forgive Larry, but Larry would never forgive him. Funkhouser is that member of the clique who cannot afford to risk his inclusion. He isn’t famous, and he isn’t fun. Larry’s connections to fellow celebrities like Lewis and Danson, and to insiders like Jeff, possess a certain logic—that of industry and reputation. Bob Einstein, who in Hollywood fact is brother to Albert Brooks and began his career with an Emmy win as a writer for The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, could certainly appear on Curb as “Bob Einstein,” but he doesn’t. He disappears into Marty Funkhouser, a born loser no matter what his bank account or synagogue tickets suggest. He is an everyman who managed to claw his way into a constellation of stars, and he isn’t giving up his spot, regardless of what it costs him. As a result, he comes to resemble a beacon of Larry’s undeclared shame. Surely it’s no coincidence that Larry, childless in the show, is frequently sparring with a man who prides himself on family values. Or that Larry berates Funkhouser, who is sixtyish, for calling himself an orphan, when just a season before, Larry had celebrated the possibility that he’d been adopted as a child.

In fairness to Larry and sourballs like him, Funkhouser is not always right, which prevents their dyad from spinning in one direction too long. A cardinal rule of Curb is that Larry does have a salient case about half the time he embarks on some idiotic, trifling crusade,  and Funkhouser obliges this artifice by heightening his morals to an absurd threshold—as when he preposterously resists Larry’s demands to hear a killer golf tip imparted to Funkhouser by a local weatherman. If Green is the id, and Larry is the ego, Funk is the super-ego, so that everyone remains in a boiling controversy. Curb plausibly asserts, as Seinfeld did, that these internecine quibbles make up the fabric of civilization, and are maybe worth hostile debate in situations where some choose diplomacy. Larry’s tragic flaw is that when he’s got the high ground, he’s still insufferable, and too late discovers why his position is indefensible. Especially to Funkhouser, Larry’s faux pas are rarely as awful as his manner of acting like they were noble.

and Funkhouser obliges this artifice by heightening his morals to an absurd threshold—as when he preposterously resists Larry’s demands to hear a killer golf tip imparted to Funkhouser by a local weatherman. If Green is the id, and Larry is the ego, Funk is the super-ego, so that everyone remains in a boiling controversy. Curb plausibly asserts, as Seinfeld did, that these internecine quibbles make up the fabric of civilization, and are maybe worth hostile debate in situations where some choose diplomacy. Larry’s tragic flaw is that when he’s got the high ground, he’s still insufferable, and too late discovers why his position is indefensible. Especially to Funkhouser, Larry’s faux pas are rarely as awful as his manner of acting like they were noble.

By holding Larry in his tightly prescribed circle—by preserving their bond through the type of social expectations Larry finds annoyingly entrenched but above all arbitrary and dumb—Marty Funkhouser sows discord in himself and for his family. Curb, insofar as it presents Larry’s finicky vantage, makes us believe that Funkhouser and his kin are rather bland hangers-on, yet it’s they who need to be rid of Larry, permanently. None of them deserve his presence. None of them deserve this asshole as a supposed friend, least of all their insulted, upstanding, and way-soft-hearted patriarch. Poor Funkhouser. His crime is wanting a nicer version of Larry’s smug comfort, but his sentence is the actual Larry, and he just keeps coming back for more.

Miles Klee is the author of Ivyland, a novel, and True False, a story collection. His short fiction, essays, and more have appeared in Vanity Fair, Electric Literature, Vulture, Guernica, McSweeney's Internet Tendency, Lapham's Quarterly and elsewhere. He lives in California.

Miles Klee is the author of Ivyland, a novel, and True False, a story collection. His short fiction, essays, and more have appeared in Vanity Fair, Electric Literature, Vulture, Guernica, McSweeney's Internet Tendency, Lapham's Quarterly and elsewhere. He lives in California.

~