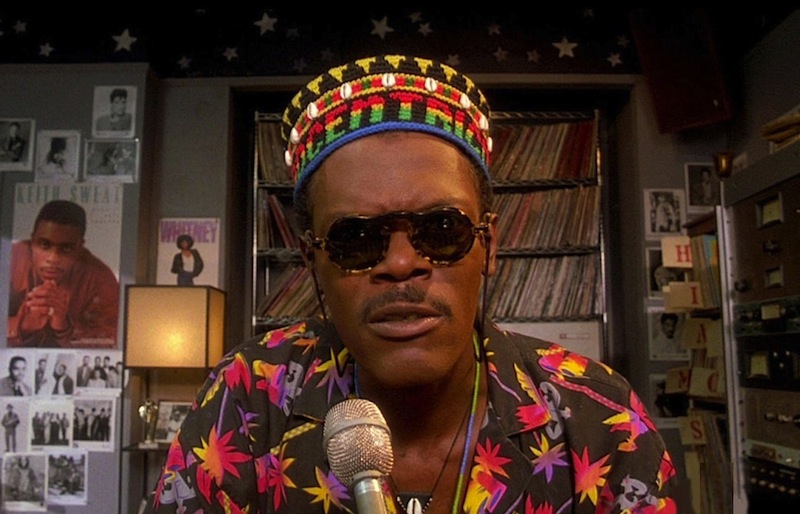

Samuel L. Jackson as

Mister Señor Love Daddy in

Do the Right Thing (1989)

by José Vadi

A Greek chorus in Brooklyn. Not your Uncle but your Uncle’s sometimes degenerate friend. A referee. A trivia game answer sheet with a pulse. A deity. A watchful eye. An informer of culture, news and soundtrack to all: Mister Señor Love Daddy is posted at the last spot on your dial but the first place in your hearts in Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing.

A Greek chorus in Brooklyn. Not your Uncle but your Uncle’s sometimes degenerate friend. A referee. A trivia game answer sheet with a pulse. A deity. A watchful eye. An informer of culture, news and soundtrack to all: Mister Señor Love Daddy is posted at the last spot on your dial but the first place in your hearts in Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing.

“Waaaake up! Up ya wake! Up ya wake! Up ya wake!” Love Daddy proclaims at the start of the film and his twelve-hour WE LOVE Radio shift. “Here I am. Am I here? Y'know it! It ya know. This is Mister Señor Love Daddy, doing the nasty to ya ears, ya ears to the nasty. I'se only play da platters dat matter, da matters dat platter and that's the truth, Ruth.”

From jump, Love Daddy’s telling Bed-Stuy what to do—WAKE UP—and through his lexicon of pre-scripted body shots and quick quips how to get up with style. Before the crust is out of the eyes of Mother Sister or the Italians not living in the neighborhood, or Sweet Dick Willy’s put on his bamboo fedora, Love Daddy’s up with news, weather, and the first songs you’ll hum on the bus or train to wherever the hell you gotta be.

Love Daddy is capable of delivering commentary in liner-note-meter of the soul records he spins by requests for locals like Mookie. He has a stunning ability of combining the dozens played by experts Slick Dick Willy and Co., sitting and sweating across from the Korean grocer, and his own free verse.

Maybe this is the kinda neighborhood DJ that Spike Lee, growing up in nearby Fort Greene, hoped he would become. Love Daddy is vigilantly aware of the catastrophic threats posed by hot days, his quasi-satirical Jheri Curl alerts beamed to his core demographic still trying to style on ‘em like a Shalimar record cover. Like his voice, Love Daddy’s wardrobe is all natural: no conk, no process, no Marcell hair-do. Just natural naps underneath a Kufi. Or a forester’s hat. Or something else. The man has more wardrobe changes than The Floaters.

In this Brooklyn we envision a young Donte Smith or Talib Kweli posted with OGs like Love Daddy, playing on the stoop outside the WE LOVE Radio station, admiring Love Daddy’s Dashikis, teasing Mookie for always being late with the chicken parm with extra s-s-s-sawwce.

The actor playing Love Daddy, Samuel L. Jackson, then the aspiring Sam Jackson, first met Lee after a 1981 performance of A Soldier’s Play before landing roles with Lee in School Daze (1988) and later Do the Right Thing while still in the throes of heroin and later cocaine addiction. It was not until Jackson completed rehab, ostensibly to play the role of a junkie in Lee’s Jungle Fever that Jackson found fame and his own niche on screen. The Cannes Film Festival created the Supporting Actor category in honor of Jackson’s timely and ironic casting and performance in this film.

The actor playing Love Daddy, Samuel L. Jackson, then the aspiring Sam Jackson, first met Lee after a 1981 performance of A Soldier’s Play before landing roles with Lee in School Daze (1988) and later Do the Right Thing while still in the throes of heroin and later cocaine addiction. It was not until Jackson completed rehab, ostensibly to play the role of a junkie in Lee’s Jungle Fever that Jackson found fame and his own niche on screen. The Cannes Film Festival created the Supporting Actor category in honor of Jackson’s timely and ironic casting and performance in this film.

The unspoken battles with substance abuse underlying Jackson’s casting and performance highlight how he, like Love Daddy, is still a product of his environs, in the sense that he cannot escape the heat on the block that everyone on screen endures and survives throughout the duration of the film.

Towards the beginning of the film, Love Daddy is hungry and waiting on trash ass Mookie to get him his food ASAP. Any afternoon daydreams of romance Love Daddy may have can only be soundtracked for those lovers suffering and sweltering outside: “Yes children, this is the cool out corner. We’re slowing it down for all the lovers in the house. I’ll be giving you all the help you need—musically, that is.” An impulse to scream to the mountaintop in the coolest voice possible all the authors of black magic and art and culture reluctantly woven into Betsy Ross’ flag hits Love Daddy out of the blue. An off-top roll call elicits some of the greatest minds and artists of African American culture, from the blues to jazz to hip hop—Dexter Gordon, Sam Cooke, Parliament Funkadelic—with Love Daddy concluding, “We wanna thank y’all for making our lives just a little brighter here on WE LOVE Radio.”

The movie begins and ends with the Love Daddy’s sermons as if they were the familiar nighttime stories delivered by our parents or the omniscient voice of God only recognizable to Bed-Stuy locals. As neighborhoods change and evolve like the residents that call them home, the question arises: who’s not only doing the play-by-play, but remembering the events of the neighborhood? Indeed, the question bears perennial repeating: who is watching over us, as opposed to surveilling us?

And that idea of the “us” is at the crux of Lee’s film, one devoid of a marquee Hollywood actor carrying us to the cinematic promised land. Instead it’s Brooklyn itself that’s in front of the camera. Mookie and Sal might be on the VHS box cover, but it’s the many side characters composing the ensemble—the infamous Buggin Out; the white Celtics fans who turns out to be a native Brooklynite; Smiley and his photos of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr.—that illustrate the underpinnings of the riots that break out at the end of the film: an attack against one is an attack against all.

With an ensemble as big and interconnected as this one, there are very few moments in the film when a character is alone; they are going from one place to another, one crew to another, to and fro either side of the block. And when those characters are in isolation it is in moments of deep contemplation—Mookie taking a breather on the hot summer steps while delivering pies; Mother Sister sitting in her windowsill. She is alone, yet she is always watching streets that are never empty.

Love Daddy—always isolated but always on air and always heard / never alone—plays arguably the most central role of the film amidst its many events, leveraging the birds eye view of the role of narrator with that of the broadcaster, the MC, the party’s catalyst, the stylized leader and informer of the Bed-Stuy he too calls home.

From old tracks to new hits, what Love Daddy knows is knowing itself: who to play, when to play and always, for whom these songs mean the entire world. Who knows when to put a roll call down in the middle of a blazing hot summer day, almost saying to himself Fuck Sal! just like Mookie, who dips back home in the middle of a sweltering summer work shift for a quick shower, like a middle-finger-respite in the name of cooling and feeling human.

Yet Love Daddy exists within a film marked by a chaotic and violent ending still debated today but not for reasons of obvious chaos and violence—Why did Mookie throw the garbage can? is still the first question asked, as opposed to Why did the NYPD choke Radio Raheem to death.

Still, after Mookie collects wages from a dejected Sal, Love Daddy begins his twelve-hour shift, almost an ethereal worker clocking in according to a measurement of time and space altogether temporal and undefined. Love Daddy’s on the air regardless, a soldier in the battle between Love and Hate formerly waged across Radio Raheem’s gold-plated knuckles, sonically beating the shit out of hate with love.

Still, after Mookie collects wages from a dejected Sal, Love Daddy begins his twelve-hour shift, almost an ethereal worker clocking in according to a measurement of time and space altogether temporal and undefined. Love Daddy’s on the air regardless, a soldier in the battle between Love and Hate formerly waged across Radio Raheem’s gold-plated knuckles, sonically beating the shit out of hate with love.

“My people my people what can I say? Say what I can. I saw it, but I didn't believe. I didn't believe it what I saw. Are we gonna live together? Together are we gonna live? This is your Mister Señor Love Daddy talking to ya from WE LOVE Radio 108 FM on your dial, and that’s the triple truth, ruth. Today’s weather? HOT...WAKE UP!”

He recites the mayor’s boilerplate statement detailing some blue ribbon panel committee, a statement with no mention of Raheem’s death or police implication. Love Daddy cracks about whether the city’s Mayor should meet the blocks Da Mayor “and buy him a beer.” He encourages the young people who previously called Da Mayor a drunk to register to vote, to empower themselves, to have a voice. This, coming from Bed-Stuy’s internal monologue itself, the motivation behind a working class Sisyphus not climbing so much as inching forward, getting by in a neighborhood waking up to rubble and caskets and stickball and heat.

Because there is no other choice but to rise.

Because the color of the day is black, because there is breath in my lungs, and because there are those from the blocks we call home that still watch over us, speak to us, waiting to see who we’ll become—and at that moment—what songs needs to be played.

José Vadi is a writer and film producer based in Oakland, California. Vadi has produced films in some unique settings, including a documentary in one of America’s largest bankrupt cities and poetry films in one of America’s most famous porn sets. The recipient of the San Francisco Foundation's Shenson Performing Arts Award, his writing has most recently appeared in Prelude Magazine, Berkeley Poetry Review, HOLD: a journal, Catapult and The Los Angeles Review of Books.

José Vadi is a writer and film producer based in Oakland, California. Vadi has produced films in some unique settings, including a documentary in one of America’s largest bankrupt cities and poetry films in one of America’s most famous porn sets. The recipient of the San Francisco Foundation's Shenson Performing Arts Award, his writing has most recently appeared in Prelude Magazine, Berkeley Poetry Review, HOLD: a journal, Catapult and The Los Angeles Review of Books.

~