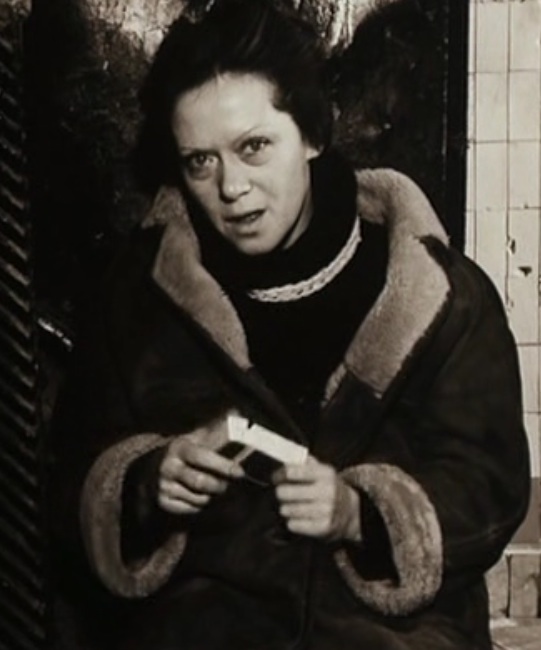

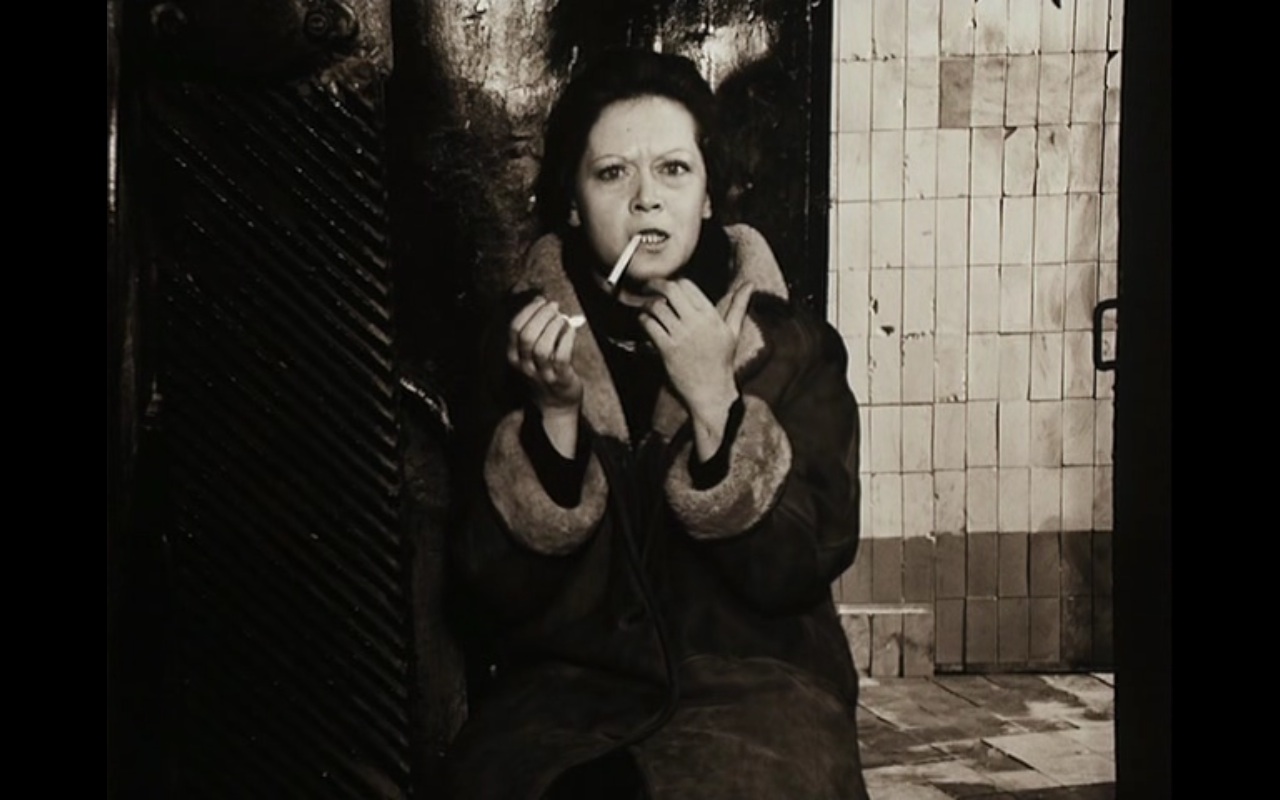

Alisa Freindlich as

Stalker's Wife in

Stalker (1979)

by Jae Towle Vieira

I was fortunate enough to watch Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker for the first time in Portland’s Cinema 21, an indie theater with significant offbeat cred. They show Tommy Wiseau’s The Room once a month, and they’ve brought out a whole slew of cult names to speak about their work in person, including Miranda July, Richard Linklater, Steven Soderbergh, and Wim Wenders. I was told Stalker was a juggernaut of a film, a slow-moving mindblower, and I did not wander out into the light three hours later disappointed. Stalker is a beautiful film—thoughtful, haunting, memorable. Its long shots and its myriad reflections of choppy water lingered with me for weeks afterward. The logistics of the journey undertaken by the protagonists—a journey both literal and figurative, magical and mundane, with rules as brutally strict as those of a fairy tale—charmed me so deeply that for days I was furious that I would never be able to use the bolts in a story of my own. In order to cross the mysterious Zone—in order to test whether the terrain is safe—the Stalker ties three long strips of white cloth to three heavy metal bolts, which he swings overhead before releasing to soar along the desired trajectory. The simultaneous meaning and meaninglessness of this method of assuring that the path is safe is gorgeous in a crystallized, archetypal way, and so much of Stalker achieves the same kind of glory, balanced on the line between significance and chaos.

I was fortunate enough to watch Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker for the first time in Portland’s Cinema 21, an indie theater with significant offbeat cred. They show Tommy Wiseau’s The Room once a month, and they’ve brought out a whole slew of cult names to speak about their work in person, including Miranda July, Richard Linklater, Steven Soderbergh, and Wim Wenders. I was told Stalker was a juggernaut of a film, a slow-moving mindblower, and I did not wander out into the light three hours later disappointed. Stalker is a beautiful film—thoughtful, haunting, memorable. Its long shots and its myriad reflections of choppy water lingered with me for weeks afterward. The logistics of the journey undertaken by the protagonists—a journey both literal and figurative, magical and mundane, with rules as brutally strict as those of a fairy tale—charmed me so deeply that for days I was furious that I would never be able to use the bolts in a story of my own. In order to cross the mysterious Zone—in order to test whether the terrain is safe—the Stalker ties three long strips of white cloth to three heavy metal bolts, which he swings overhead before releasing to soar along the desired trajectory. The simultaneous meaning and meaninglessness of this method of assuring that the path is safe is gorgeous in a crystallized, archetypal way, and so much of Stalker achieves the same kind of glory, balanced on the line between significance and chaos.

In Stalker, occupations act as names. Our protagonist is Stalker, the guide on whose expertise the other primary characters rely to traverse the Zone. The Writer and the Professor have paid Stalker handsomely for his services, and acquiesce to the Stalker’s insistence that their real names go unused. As with many other aspects of the film, including the radioactive jungle of the Zone and the ominous wish-granting Room that lies somewhere deep within, this synecdoche invites allegorical readings: the Writer’s behavior provides a commentary on that man as an individual but also on writers, the Professor grapples with problems belonging to both his position and the academy at large, and our Stalker is characterized predominantly by his zealotry. He’s after something, and the chase defines him. I’ll be writing about Stalker’s wife, who has no other name. (In the original Russian, she’s listed as Zhena Stalkera: Stalker’s wife, or Stalker’s woman.) She does not accompany the others to the Zone. Most of her scenes take place at home. If you feel as though you already know what I’m going to say, I hope that’s accompanied by a precognitive familiarity with all of Stalker’s wife’s potential arcs. You know what it means to be the wife of a man with a larger calling.

She appears twice in the film, once at the beginning and once at the end. We see her begging her husband not to return to the Zone, which is cordoned off and heavily guarded—begging him to think of his own well-being. If he won’t stay behind for his own sake, she asks him to think about her and about their child, who is unable to walk and needs special care. He has only just been released from prison, presumably for the crime of helping people sneak into and out of the Zone. Naturally, he doesn’t listen to her—he informs her that for him, “everywhere” is a prison—and he leaves to meet the Writer and the Professor at a bar.

In a review for the Guardian, critic and writer Geoff Dyer, who has written a full book about the film, encapsulates the way in which the audience is expected to read the allegorical wife. His summary of the film’s first fifteen minutes includes such lines as: “The film’s only just started, she has just woken up and, from a husbandly point of view, she is nagging. No wonder he wants out!” and “The wife expands on this notion of time—she has lost her best years, grown old—and you're reminded again of Antonioni, because the plain truth is, she's no Monica Vitti,” and “After the Stalker leaves, his wife has one of those sexualised fits of which Tarkovsky seems to have been fond, writhing away in a climax of abandonment. He, on the other hand, like many men before and since, has gone to the pub.” I’m struck by the hair-scruffing benevolence of Dyer’s tone: boys will be boys, won’t they, men men and wives wives. Dyer aptly demonstrates his awareness of the tropes at play, but the meat of his analysis lies elsewhere; he’s as happy as Tarkovsky to cross the threshold into adventure and leave the nagging wife behind.

Dyer’s descriptions of Stalker’s wife reminds me of the thinkpiece hubbub surrounding Breaking Bad’s Skyler White, played by Anna Gunn. See “Why You Hate Skyler White” or “How Better Call Saul Fixed Breaking Bad’s Skyler Problem.” Anna Gunn’s own editorial on the subject, “I Have a Character Issue,” deserves a look; she reckons with fans’ responses as both “an actress” and “a human being.” In the article about “Fix[ing] Breaking Bad’s Skyler Problem,” Lili Loofbourow theorizes that the virulent hatred many fans felt for Skyler—which Vince Gilligan and the other writers apparently did not intend to evoke—was the result of “a structural problem,” adding that “The great antihero experiment yielded what I like to think of as the Gilligan Theorem: Protagonism, no matter how villainous, easily trumps ethics. A corollary to that theory is that people love momentum, morals be damned, and turn on characters who try to pump the brakes. Particularly when they're women.” And again, I’m stymied by the question of whether it’s necessary to make the obvious points. Stalker’s wife is a minor character; sometimes minor characters are women; sometimes spouses disagree about the best course of action; sometimes somebody has to stay home; and even so, despite my affection for Stalker and my respect for Tarkovsky, watching Stalker’s wife writhe in the snare of her own life makes my own ribs ache.

My failings and insecurities are bleakly cliché. I don’t want to be rejected. I’m afraid of conflict. I’m constantly trying to be as pleasing as possible by whatever metric I assume the other person wants—which works sometimes, and sometimes makes me seem obsequious, and sometimes misses the mark completely, since people don’t always want what I think they want, and because sometimes other people do seem to want me to be “myself.” I’ve been told several times by several men—men who did and do sincerely care for me—that my “only problem” is my lack of confidence. I’d phrase it differently, I think. They probably meant to refer to my tendency to fall into another person’s orbit, to react and respond instead of acting and speaking. (I’m stiff in parties and with strangers, which certainly resembles shyness, and sure, I’m probably also shy, but it’s hard to please multiple people at once and it’s hard to please strangers because their likes and dislikes are unknown.) Action, in life and in Stalker, is a luxury everyone can’t possess at once. We learn this lesson again and again during the film—we learn it as the men sneak into the Zone, alternating between hiding and sprinting for cover, and we learn it as the men begin to traverse the treacherous fields and waterways separating them from their goal, and we learn it at the doorstep of the Room, when the tension between the men erupts.

Stalker’s wife takes care of their daughter, Monkey, which is probably a nickname, though I suppose I can’t be sure. (It’s interesting to think about the significance of this lone almost-name amid all the others, especially in the context of the final moments, but that’d be a digression.) At the end of the film, which is bookended by domestic scenes, Stalker’s wife brings Monkey to the bar to meet Stalker upon his return from the Zone. We see Stalker’s wife help Monkey to a bench before she greets her husband. I’m sure the Geoff Dyers of the world won’t find this question interesting—I’m sure they believe they’ve heard it all before—but I can’t avoid it now: if Stalker’s wife wasn’t there, if the Stalker was Monkey’s sole caretaker, could he be a Stalker? Could he leave on these long trips to the Zone? Could he risk death, could he risk getting arrested? Obviously the answer is no, and yet one of the potential readings of the Stalker’s climactic crisis on the threshold of the Room revolves around Monkey, around the idea that if the Stalker were to enter the wish-granting Room himself, he’d want to help his daughter. (Or at least he’d like to believe he’d want to help his daughter—the film explicitly warns us that our deepest wishes probably aren’t virtuous or altruistic, and the Room only fulfills the genuine wish.) Does the potential that the Stalker might believe he wants to help his daughter absolve him from the breathtaking selfishness of leaving home, knowing that leaving requires his wife to stay?

In my relationships with men, especially, I tend to fall into patterns of sacrifice—little sacrifices my partners aren’t usually aware I’m making, because part of me believes that this kind of generosity constitutes love. Yes, you can have the leftovers—yes, I can pick you up at the bar at three in the morning—no, I won’t tell you when you’re bugging me—no, I won’t vent about my bad day. I am an older sister and an eldest daughter, and our family’s circumstances have often required me to be steady, thoughtful, and reliable: to have it together. One person always has to have it together—this is what allows others the freedom to stumble, question, and doubt, to feud and falter and withdraw at will. The worst years of my life were those in which I had convinced myself, post horrific-family-crisis, that the people I loved needed me to be that person. As the months passed, preserving that competence became increasingly draining, but my capacity to forego my own needs and emotions felt strangely bottomless. Of course, I didn’t need to be so strong, at least not at all times—no one had asked me, no one would ever have asked me, and as I know now, it’s possible to take turns—but through some kind of osmosis I felt it was necessary and required of me without having to be told.

In my readings about Tarkovsky—and I admit, I’m not very familiar with him or his other work, so this is an outsider’s take—he seems to valorize women as mothers above all else. Films, shows, and works of literature often characterize motherhood in these terms: ongoing steadiness, unconditional love, perpetual home-generation, having it together. Sitcoms get significant mileage from mothers and mothers-in-law: they just have so many opinions, don’t they? So frustrating, so funny, so easy to mock and to minimalize. As if caretaking to such an extent over so many years wouldn’t leave scars, as if it doesn’t do something to your relationship with yourself to be a family’s lone safety net, as if even in countries where women’s movements have made powerful progress toward equality, we aren’t still feeling the hangover from the last few decades. Stalker regularly places highly on lists of the best films of the last century and best films of all time, but for all its merits, I wonder whether this luster is poisonous.

When I try to analyze or justify my habit of self-erasure—which tended to corrode past relationships, due to the resentment that accumulated in me over time, and which, for the record, I consider to be my fault, the result of my failure to communicate—I’ll reason that partnership requires sacrifice, that the other person, if they’re as kind and good and empathetic as I want to believe they are, would do the same for me. But even if that other person would have been willing, it’s rarely happened. Compulsive sacrifice—compulsive self-relegation to an orbital state, endlessly deferring, catering, modulating—is a quality our society wants to cultivate in women, and unfortunately I’ve turned out to be a good specimen in that regard. I’m a selfish person—I’m jealous, slow to trust and to forgive, and all too willing to cleave unwanted responsibility from my life—but even so, within the context of a romantic relationship, it’s almost impossible for me to imagine being the one who gets to have a larger calling. But let’s hope relationships can accommodate more than one passion. Let’s hope domestic allegiance doesn’t have to divide agency 70/30 (or worse) when each participant is an artist. Let’s recognize that “Nabokov” was the product of Nabokov and Véra, who gave up a writing career of her own. Let’s hope relationships can take a hundred thousand forms, let’s hope the caretakers find balances appropriate to their individualities, let’s hope that everyone who wants to go to the Zone can go to the Zone and everyone who wants to stay home can stay home, and let’s hope there’s room for everyone to change their minds. Let’s hope there can be such a thing as a partnership between two Stalkers. I believe in partnership, I think, though I would hate to be somebody’s wife.

Isn’t the Zone what I ought to be talking about? Doesn’t the question of faith versus nihilism have ongoing resonance? Am I missing the point? Isn’t focusing on this woman somewhat obtuse when there’s another two hours of labyrinthine richness begging for (and doggedly evading) coherent analysis? And all I can say is yes—of course—I’d love to analyze Monkey and the dog, or the use of color, the different modes of travel within the Zone, the metal bolts with their trails of white cloth, the uncanny telephone, the recurrent water, the tension between the three travelers, time and agonizingly long shots, dream-logic and memory—but Stalker’s wife’s role in this story is neither an accident nor a coincidence. As we all know, one of the most fundamentally meaningful aspects of science fiction is its power to render social convention visible, to provide commentary or to imagine alternate frameworks, and for all the seductive magnetism of the Zone, for all the glorification of the imagination, how should I read Stalker’s wife? Which aspects of our society have been changed and which aspects have been artfully distorted and which aspects have been reproduced faithfully? Why?

We spend at least thirty-six seconds of a single shot watching Stalker’s wife crying as she writhes on the floor, as the scope narrows from the room and floorboards and her whole body to only her upper torso and face, her shaking head and her nipples, sharply evident through her thin nightgown. This cannot necessarily be said to indicate an unusual degree of emphasis—many of the shots in Stalker are long and slow and eerie, lingering well beyond the moment when the point was proven—but somehow the moment is jarring all the same. When she arches her back, when her sweater falls away to reveal her breasts more clearly, and as she sobs, I don’t know how to read her as sincere, as alone. The moment is as performative as it is private, as intimate in its pain as in its sexuality. The moment wouldn’t exist if no one were present to see it—this tree only falls in the forest because the camera is running, and this is not only true because this scene is part of a film but true within the world of the story as well. She knows we are watching, or she believes the Stalker is watching, literally or figuratively—somehow she knows she is not alone. Over the course of those thirty-six seconds, I begin to see a doubling in Stalker’s wife: one self pleads with the Stalker to stay home, and one self, aware of herself as a component of a film, aware of herself as bookend, has another objective.

We spend at least thirty-six seconds of a single shot watching Stalker’s wife crying as she writhes on the floor, as the scope narrows from the room and floorboards and her whole body to only her upper torso and face, her shaking head and her nipples, sharply evident through her thin nightgown. This cannot necessarily be said to indicate an unusual degree of emphasis—many of the shots in Stalker are long and slow and eerie, lingering well beyond the moment when the point was proven—but somehow the moment is jarring all the same. When she arches her back, when her sweater falls away to reveal her breasts more clearly, and as she sobs, I don’t know how to read her as sincere, as alone. The moment is as performative as it is private, as intimate in its pain as in its sexuality. The moment wouldn’t exist if no one were present to see it—this tree only falls in the forest because the camera is running, and this is not only true because this scene is part of a film but true within the world of the story as well. She knows we are watching, or she believes the Stalker is watching, literally or figuratively—somehow she knows she is not alone. Over the course of those thirty-six seconds, I begin to see a doubling in Stalker’s wife: one self pleads with the Stalker to stay home, and one self, aware of herself as a component of a film, aware of herself as bookend, has another objective.

At the end of the film, after Stalker’s wife brings him home from the bar, dries his tears, listens to his frenetic rambling, and helps him into bed—and after she offers to help him through his crisis of faith, or his crisis of faith in other people’s faith, by accompanying him into the Zone herself, and after he tells her no—she speaks directly to the camera. The shift was startling—when she looked into the lens, I became conscious of my body in a way I hadn’t been for hours, and I was reminded of the film’s own self-consciousness. I appreciated the boldness of the move—I wanted to know what the film wanted me to believe with such urgency. As she spoke, however, I lost the last of my trust in her. I began to feel that she was answering an as-yet unspoken critique—she became someone else’s mouthpiece. The best transcription I’ve found so far translates her speech like this:

At the end of the film, after Stalker’s wife brings him home from the bar, dries his tears, listens to his frenetic rambling, and helps him into bed—and after she offers to help him through his crisis of faith, or his crisis of faith in other people’s faith, by accompanying him into the Zone herself, and after he tells her no—she speaks directly to the camera. The shift was startling—when she looked into the lens, I became conscious of my body in a way I hadn’t been for hours, and I was reminded of the film’s own self-consciousness. I appreciated the boldness of the move—I wanted to know what the film wanted me to believe with such urgency. As she spoke, however, I lost the last of my trust in her. I began to feel that she was answering an as-yet unspoken critique—she became someone else’s mouthpiece. The best transcription I’ve found so far translates her speech like this:

You know, my mother was against it. You've probably noticed already that he's not of this world. All our neighborhood laughed at him. He was such a bungler, he looked so pitiful. My mother used to say: “He’s a stalker, he’s doomed, he’s an eternal prisoner! Don’t you know what kind of children the stalkers have?” And I... I didn’t even argue with her. I knew it all myself, that he was doomed, that he was an eternal prisoner, and about the children. Only what could I do? I was sure I would be happy with him. Of course, I knew I’d have a lot of sorrow, too. But it’s better to have a bitter happiness than a gray, dull life. Perhaps I thought it all up later. But then he approached me and said: “Come with me.” And I did, and never regretted it. Never. We had a lot of sorrow, a lot of fear, and a lot of shame. But I never regretted it, and I never envied anyone. It’s just our fate, our life, that’s how we are. And if we haven’t had our misfortunes, we wouldn’t have been better off. It would have been worse. Because in that case, there wouldn’t have been any happiness. And there wouldn’t have been any hope.

I’m skeptical of this move, although I’d love to be able to take her at her word. It’s certainly possible to choose to stay home, to caretake and to have no regrets. Some of my orbital phases have been acts of freely given, conscious love, and I am so thankful for the people who have loved me that way. But the choice to give her such a monologue at the end of the film, and to have her address it to the camera—the choice to leave her justifying the Stalker’s choices, as if her complaints from the beginning weren’t legitimate—seems suspect to me. In some ways this feels like a fantasy, the most self-aggrandizing combination of wife tropes from the perspective of the male-hero figure: she’s in (sexualized!) agony when I leave, and fiercely protective of me when I come home, and although our life together is miserable for her, she’s overflowing with the need to tell the world she wouldn’t have it any other way. In his detailed review of the film, Matthew Pridham argues that “If Tarkovsky identifies with anyone in this film, it is obviously the Stalker: a frustrated poet, a man haunted by what he is leaving future generations and how much better a job he could have done.” If that’s a reasonable take—and I’m inclined to believe it is, given that the film privileges the Stalker’s stance on life/faith/etc. above the others’—ending on a self-exoneration seems ethically suspect. But perhaps I’m projecting. Maybe Stalker’s wife truly does see her husband as the “eternal prisoner” in this scenario. Stalker fans do tend to talk up how much room Tarkovsky leaves for you to form your own interpretation.

Jae Towle Vieira grew up between forest fires. She has an MFA from the University of Arizona. Her fiction has appeared in Carve, Eleven Eleven, The Normal School, and Passages North. She features strong violence throughout, some language, and partial nudity.

Jae Towle Vieira grew up between forest fires. She has an MFA from the University of Arizona. Her fiction has appeared in Carve, Eleven Eleven, The Normal School, and Passages North. She features strong violence throughout, some language, and partial nudity.

~