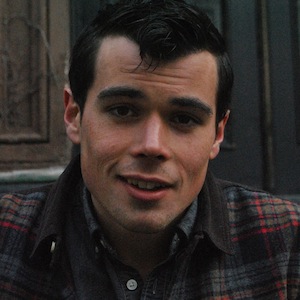

Anthony Edwards as

Nick “Goose” Bradshaw in

Top Gun (1986)

by Devin Kelly

A flat spin is how it begins. A flat spin is an unrecoverable form of a tailspin. A flat spin involves things getting worse quickly. A flat spin turns the plane on its own axis as it falls through the sky. A flat spin requires the plane’s inhabitants to eject. A flat spin, because of its aggressive nature, might render the plane’s inhabitants incapacitated and thus unable to eject. A flat spin sometimes feels like life, and by that I mean that life sometimes feels like a flat spin. A flat spin represents the worst of things, a scenario where disaster is almost always the outcome. A flat spin abides by the rules of physics and not free will. A flat spin is distance over time. A flat spin is birth and then death. A flat spin does not listen and does not care. A flat spin, you say, I feel like I am in a flat spin, and I hold you and do not know if this helps or not, your body in my arms and how I feel your heart beating and how I do not know if beating is a kind of spinning, your skin sticking to mine, each of us trembling, our bodies weighed down by gravity.

A flat spin is how it begins. A flat spin is an unrecoverable form of a tailspin. A flat spin involves things getting worse quickly. A flat spin turns the plane on its own axis as it falls through the sky. A flat spin requires the plane’s inhabitants to eject. A flat spin, because of its aggressive nature, might render the plane’s inhabitants incapacitated and thus unable to eject. A flat spin sometimes feels like life, and by that I mean that life sometimes feels like a flat spin. A flat spin represents the worst of things, a scenario where disaster is almost always the outcome. A flat spin abides by the rules of physics and not free will. A flat spin is distance over time. A flat spin is birth and then death. A flat spin does not listen and does not care. A flat spin, you say, I feel like I am in a flat spin, and I hold you and do not know if this helps or not, your body in my arms and how I feel your heart beating and how I do not know if beating is a kind of spinning, your skin sticking to mine, each of us trembling, our bodies weighed down by gravity.

After the flat spin, and the subsequent ejection, Goose’s body hangs from the cords of his parachute, the silhouette of it navy-dark, perched affront that place where sea meets sky. Goose’s neck slumps forward, away from the camera, as if drinking from the horizon line. The body, slack, seems to pull the chute quicker into the ocean. He lands before Maverick does, in a pool of orange and green, blood and water and canvas and rope. Just seconds before, Goose yanks the eject handle. The plane is in a flat spin, engines stalled, the billion dollars worth of metal twirling like a stiff dancer out into the ocean.

Why him, I ask, it should be Maverick. But Maverick can’t reach. It can’t be Maverick, anyway. He’s too small. He has too much to prove. His story is not done yet. Still, I push back tears. They repeat the same things about people who die young, about the rockstars and mavericks of the world. They say that they were bursts of light, exploding stars. Goose’s life is too beautiful to last.

I never know, really, if Goose dies the moment his body strikes the unopened cockpit, if he is dead when he hangs there, balanced in freeze-frame between heaven and earth, in one of the few times you can see his birth name clearly: Nick Bradshaw. If you pause the tape and play it in reverse, you can watch him ascend. Ascend into the orange light of evening, away from the sea. Ascend out of the violence of contact, back into the safety of the cockpit. Ascend away from the dogfight. Ascend down upon the runway. Ascend into the life well lived, the family gathered round the piano, the song of it.

When Maverick, floating, finds Goose, it is already as if Goose’s body is prepared for burial, the parachute a kind of winding sheet, shroud. Maverick pulls and untwists the material that has a body caught within it. I’ve always been struck by this moment, how fraught and confused it is. In it, Maverick, reaching and wriggling and contorting, is reduced, finally, to someone so much smaller than what he tries to be. The ocean around him is large. The death he faces is larger, and less easily understood.

The word wind means so much, as noun and verb, as a thing prefixed and addendum-ed. To be wind is to be as air, to be invisible and free and both gentle and harsh, a source of power but also a source of unseen alteration – whether it be changing the direction of a flag or propelling a ball over a fence. To wind is to be in control, to be the hand that cranks the wheel or presses that button that moves sound or picture further into that sound or picture’s past or future. All these or’s. That is the power of wind and wind. To generate the word or, a confluence of nuance. To move between things, between past and future. To refuse simple dwelling.

So we eject. We rewind. We move forward or back, but never settle. Einstein supposedly writes, “No worthy problem is ever solved within the plane of its original conception.” So we leave that the first plane, the one spinning out toward sea. We leave as wind does, through or between that small gap we are allowed. We leave one plane for another, and another, and another. Because there is never not a problem to solve.

~

I am obsessed with Top Gun because I have always been, after having watched the movie with my father at some point in the single digit years of my lifetime. Back then, my father used to call me Maverick. Get in the game, Maverick, he shouted from the sidelines of baseball games and soccer fields and basketball courts. He meant it well, as a gentle prodding, knowing that I harbored vague Napoleonic tendencies, never feeling whatever-enough to succeed. Tall. Skinny. Cute. Mean. Nice. We watched Top Gun too often, sometimes once a week, and in those younger years I turned toward Maverick as inspiration, finding in his dark sunglasses and trim haircut an appeal I couldn’t shake. Goose, to me, was the buddy in the background, forever tagging along, and then later, as if by necessity, left behind.

Growing up, I was always the too-chubby kid at the pool party, always feeling like I had something to hide. I learned how to swim too late in life, and wore a t-shirt and big orange floaties around my arms. I sat on the edge of the pool, my feet in the water. In the infamous volleyball scene, Goose, Maverick, Iceman, and Hollywood, each shirtless, stand sleek and glittering, wet and warm in the dusky sun. Goose always seems surrounded, or, at the very least, never alone.

I started watching the movie alone, without my father, in the years after my mother left. I was still Maverick to my dad, but it was then that I began longing to be Goose. Just over an hour into the movie, Goose sits at the piano, his son perched atop, and together they erupt in a goofy, energetic rendition of “Great Balls of Fire.” Years after originally watching the movie, I stand outside a bar before a night of Tuesday trivia, scrolling through Top Gun facts online to further, I hope, enhance my mastery of the subject in the event that it’s ever tested (that night, it wasn’t). It’s then that I learn that the aforementioned scene wasn’t originally supposed to happen in the movie, but each time I watch it now, I wonder how could it not? It’s relentless and corny and tender and full of magic, but it’s also jingoistic as hell – a Budweiser set atop the instrument, a cowboy hat beside it, the son white and blonde and donned in a kid-sized cowboy hat as well.

Even still, Goose’s charm is contagious. He wears a festive blue oceanic button down, and carries the song with primal yelp that is less singing than shouting. Each appearance Goose makes in the movie urges me to want him there just as beautiful, and twice as long. When he disappears, he becomes more winding sheet than parachute, signaling the long dirge rather than the rescue, reminding us that it was Maverick’s story all along.

So when Maverick ambles over to join him beside the piano, he almost ruins the moment. He’s too preened. Beautiful. Clean. He stands too stiffly beside Goose, unwilling to truly belt the words. He reaches for the child and plays with him the way he would play with someone else’s puppy if, deep down, he was really a lover of cats.

In a 2012 New Yorker profile of Bruce Springsteen, David Remnick writes of Springsteen’s “anti-ironical” qualities, using Keith Richards as a foil. In contrast to Springsteen’s “flagrant exertion,” there is Keith Richards, who, Remnick writes, “works at seeming not to give a shit. He makes you wonder if it is harder to play the riffs for ‘Street Fighting Man’ or to dangle a cigarette from his lips by a single thread of spit.” I’ve always loved this comparison, and it makes me think of Maverick and Goose – one so caught up in the performance of his masculinity, the other so caught up in the performance of life. In an age where the forever-toxic aspects of masculinity are being continually called out, I look toward Goose – just as Remnick looks toward Springsteen – as an example of someone who cherishes life so much that his performance through it transcends the notion that societal conceptions of masculinity should be used to define and emphasize one’s maleness. In fact, I don’t know if Goose is performing at all; rather, he’s comfortable enough with himself to simply live. When Goose, in his own moment of flagrant exertion, belts out “Great Balls of Fire,” he is singing as man, husband, and father, yes, but he is singing first and foremost as Goose, someone who no longer fears how he became himself.

As a child, I came home from school, laid my homework out on the couch in front of the television, and, alone, wound and rewound this scene at the bar. I watched the carelessness of Carol (Meg Ryan) and Goose’s love, how she pops food into her mouth and floats come-on’s to her husband. Take me to bed or lose me forever, she yells across the bar, mouth open, eyes wide and shimmering. Show me the way home, Goose manages, before returning to the song and his son.

I’m 11, 12, 13 years old when I obsess over this moment. I’m sitting on the couch at home alone, pausing the movie, whispering to no one in particular: Take me to bed or lose me forever. I’m putting on my father’s cowboy hat in the mirror of the bathroom. I’m tilting my head back, I’m saying: show me the way home, honey. I’m falling in love with this performance of love, how, in the grip of it, it feels like the only thing worth pursuing.

It’s interesting to note that the bar where they filmed this scene burned down years after the movie was made. One of the only items that survived was the piano where Goose played. I imagine the fire hissing along the wood floor, the bartop, the chairs and tables, until it reaches the piano, where, like flaming oil surrounding a circle of ocean, it makes its own halo out of its inability to touch.

The next scene, Maverick and Charlie kiss on a motorcycle and everything is sexy and sheened, but I want a split-screen, the finished song, the child on the piano. The kiss, the straddled vehicle, the ocean breeze, the take-my-breath-away – all of that can stay, but I want to feel the need to sing, to belt, to stammer and yelp. To have someone worth singing to, mistakes and all. I want to watch Goose and Carol after Maverick left the bar, watch them take the child with them and put him to bed early even if he’s not tired at all. I want all the small nuisances that love brings.

As I write, I am propped up on pillows next to the woman I have been dating and loving for over a year. At dinner today, we joked as we often have lately about future children and their names, which I’ve heard you shouldn’t do if you want to have any hope of living in the present moment of a relationship without any worry of what the future will bring, or what it won’t. But I’ve done this with everyone I’ve ever loved in the short time I’ve been around, chasing the terror and comfort of being with someone who can offer levity to the future, which, I’m realizing as I watch Goose’s death again, is always more mystery than surety.

Younger, I dreamed of a Maverick future. I loved the notion of being the best at something, of being in complete control. Maverick’s sharp glances to the side, his mythos and rebellion – these things were attractive. I don’t know how you grow out of that or if you do. I watched the movie by myself, mother gone and father not home until late, and thought in Maverick’s terms: I can carry myself because no one cares but me. I insisted upon doing everything on my own and sometimes still do. When I was younger and my father offered to help me with anything, I struck his body and ran away. The myths to which we attach ourselves can be so strange in how they prevail to become the dominating forces in our lives.

Tonight, though, I am so lovingly caught in the tender orbit of someone else’s care. But even love, too, is terrifying. It offers another death of which to worry. It gives the future a gentle kindness and an evil name. I sit here in the calm of someone else’s breathing. She has pulled off the blankets and made them hers. I will not take them back.

I pause the movie every time Goose’s body – lanky and goofy and mustached – is frozen on the screen. Every time I rewind, I hope it will become someone else’s story. I doubt it will. But I’m scared of endings. Moving backward from Goose’s death, there is no longer a loss each time I see him on the screen. It is a kind of miracle. I know the future will eventually end this new thing my lover and I have. What or who we are might depart in the middle of the night, without warning, the way each day of our living makes ghosts of our past selves. Goose looks at Maverick as Maverick puts on his shirt to leave the game. Maverick is always moving toward the next endeavor, throttle steadily throttling upward, the plane forever ascending. Goose just wants to stay here for a little while, for this little while that he can. I get it. It all ends. The game, these friendships, our lives. Who sees this? Who talks about this at all?

I pause the movie every time Goose’s body – lanky and goofy and mustached – is frozen on the screen. Every time I rewind, I hope it will become someone else’s story. I doubt it will. But I’m scared of endings. Moving backward from Goose’s death, there is no longer a loss each time I see him on the screen. It is a kind of miracle. I know the future will eventually end this new thing my lover and I have. What or who we are might depart in the middle of the night, without warning, the way each day of our living makes ghosts of our past selves. Goose looks at Maverick as Maverick puts on his shirt to leave the game. Maverick is always moving toward the next endeavor, throttle steadily throttling upward, the plane forever ascending. Goose just wants to stay here for a little while, for this little while that he can. I get it. It all ends. The game, these friendships, our lives. Who sees this? Who talks about this at all?

The first time we meet Goose, he is in the sky. His oxygen mask dangles off his helmet, and you can make out his mustache, trimmed and brown, decorating the top of his lip. When he smiles, wrinkles form by the sides of each eye, curling upward as if his skin is smiling, too. He’s not flying the plane. Maverick is. But still, Maverick’s first lines are talk to me, Goose, perhaps knowing that the man behind him possesses some deeper understanding of the sky and those who inhabit it. It is odd, having watched this movie in reverse, from death to birth, from ocean to sky, and to end, simply, with the words, talk to me, Goose.

~

I have been watching Top Gun for almost two decades of my life now. I have seen the movie start-to-finish at least a hundred times, and, as a kid, would sit cross-legged and patient in front of the VCR as it hummed the steady sound of the tape rewinding. Now, the process of moving backward takes just a simple click. I once got too drunk in a bar after college and began to recite the entire movie, even singing a few acapella seconds of “Danger Zone.” I understand almost everything that’s wrong about the movie, from its Cold War jingoism to its overt, crushing machismo to the simple fact that watching it is like mainlining adrenaline, but I still can’t stop taking it in. And even now, when the camera first captures Goose, it takes something both sudden and real - a pinch, the piercing clink of a glass tipping over - to remember that he’s going to die.

I see in Goose so much. I see my father and the way, in those years after my mother left, rarely but sometimes, he would let himself unwind, and I’d look up to find him charging across the room to wrestle me, or feel him plucking the hairs from my arms and legs as he sang some old song from The Band while he drove. I see the eyes of my own friends and the capability of such eyes to express disappointment, joy, shock, or sorrow. I see my face in the mirror and how I’ve learned to love and failed and have learned to love again in different ways. I don’t know if we find our best selves until we see such selves in others.

Sitting here now in the darkness, I find in Top Gun a gentleness I haven’t found in it before. Maybe it’s because I have Goose’s face paused upon the screen, all smile and grin. Maybe it’s because I think too often of my father dying; he, this man who raised and taught me, through absence and silence and the occasional softened kindness – a toenail clipped while I slept – that a person shouldn’t have any standards higher than tenderness, that I didn’t have to be anything in particular to be a man. Maybe it’s because, as I grow older, I think too often of fatherhood, and this scares me, like death, because it is both final and uncertain. Maybe it’s because I no longer long to be Maverick.

The moon’s light narrows itself through the window and shines a pale white upon the corner of my screen. I’m not tired. I make sure the volume is low enough not to wake the person sleeping next to me, and I press play, watching the movie in its intended direction for the umpteenth uncountable time. I watch everything I just watched happen, this time in another direction. I watch the first dogfight, the journey to Top Gun, the bar scenes and training missions, the sex and volleyball and music, the canned lines and improvisations. I watch Goose sit behind Maverick and then stand next to Maverick and then warn Maverick and then sing with Maverick and then die, hanging in the air, falling through the sky. I still cry. I don’t know what this movie taught me or what it’s supposed to teach, how each new viewing offers the potential to encounter what it might get wrong about men, or sex, or violence, or what I thought I had encountered fully before. It gets death right, though, how it happens suddenly – a body in the process of escape, crashing – and then how it hangs, falling slowly through the air, like grief does. When I feel like Maverick now, I feel like that Maverick, the one descending from the failed plane, watching the one he loves descending too, only trying to reach him to say goodbye, not having been taught how, never having thought he would ever have to.

Devin Kelly was born in Washington, D.C. and later moved to New York City to attend college at Fordham University before earning his MFA from Sarah Lawrence College. He co-hosts the Dead Rabbits Reading Series and is the author of two collaborative chapbooks as well as the books Blood on Blood (Unknown Press), and In This Quiet Church of Night, I Say Amen (CCM). He edits for Full Stop, works as an after-school director in Queens, teaches at the City College of New York, and lives in Harlem. While working at shoe store in college, he had the pleasure and honor of selling Reese Witherspoon a pair of running sneakers.

Devin Kelly was born in Washington, D.C. and later moved to New York City to attend college at Fordham University before earning his MFA from Sarah Lawrence College. He co-hosts the Dead Rabbits Reading Series and is the author of two collaborative chapbooks as well as the books Blood on Blood (Unknown Press), and In This Quiet Church of Night, I Say Amen (CCM). He edits for Full Stop, works as an after-school director in Queens, teaches at the City College of New York, and lives in Harlem. While working at shoe store in college, he had the pleasure and honor of selling Reese Witherspoon a pair of running sneakers.

~