Anne Louise Hassing as

Susanne in

The Idiots (1998)

by David Kuhnlein

The Idiots opens with white chalk on wood – Dogme 2: Idioterne. Cut to Karen (Bodil Jørgensen), a middle-aged redhead dressed in a flower-pleated dress several sizes too large, drunk and nervously clutching her purse. She stares at the sun as if she forgot something in the sky, her face a blank conveyance. Now Karen’s seated in a restaurant where she’s not allowed to order prawns (because she’s alone?) and she can’t afford the “salmon cheese” – whatever that is. (The English subtitles, like much of my own life, often leaves me guessing.) On the verge of tears, Karen opts for a mineral water instead of tap. It’s not clear if she really wants mineral water or if she ordered it as a courtesy to her waiter. The waiter, looking slightly unnerved from their exchange, leaves Karen alone with a basket of bread, the pieces of which she struggles to bite into. The bread is a metaphor, a slice of things to come. Karen has bitten off more than she can chew. She desperately tries to get her mouth around the loaf, already beginning to drool, and the look in her eyes tells us that her mind is elsewhere – preoccupied with the group seated in the corner.

The Idiots opens with white chalk on wood – Dogme 2: Idioterne. Cut to Karen (Bodil Jørgensen), a middle-aged redhead dressed in a flower-pleated dress several sizes too large, drunk and nervously clutching her purse. She stares at the sun as if she forgot something in the sky, her face a blank conveyance. Now Karen’s seated in a restaurant where she’s not allowed to order prawns (because she’s alone?) and she can’t afford the “salmon cheese” – whatever that is. (The English subtitles, like much of my own life, often leaves me guessing.) On the verge of tears, Karen opts for a mineral water instead of tap. It’s not clear if she really wants mineral water or if she ordered it as a courtesy to her waiter. The waiter, looking slightly unnerved from their exchange, leaves Karen alone with a basket of bread, the pieces of which she struggles to bite into. The bread is a metaphor, a slice of things to come. Karen has bitten off more than she can chew. She desperately tries to get her mouth around the loaf, already beginning to drool, and the look in her eyes tells us that her mind is elsewhere – preoccupied with the group seated in the corner.

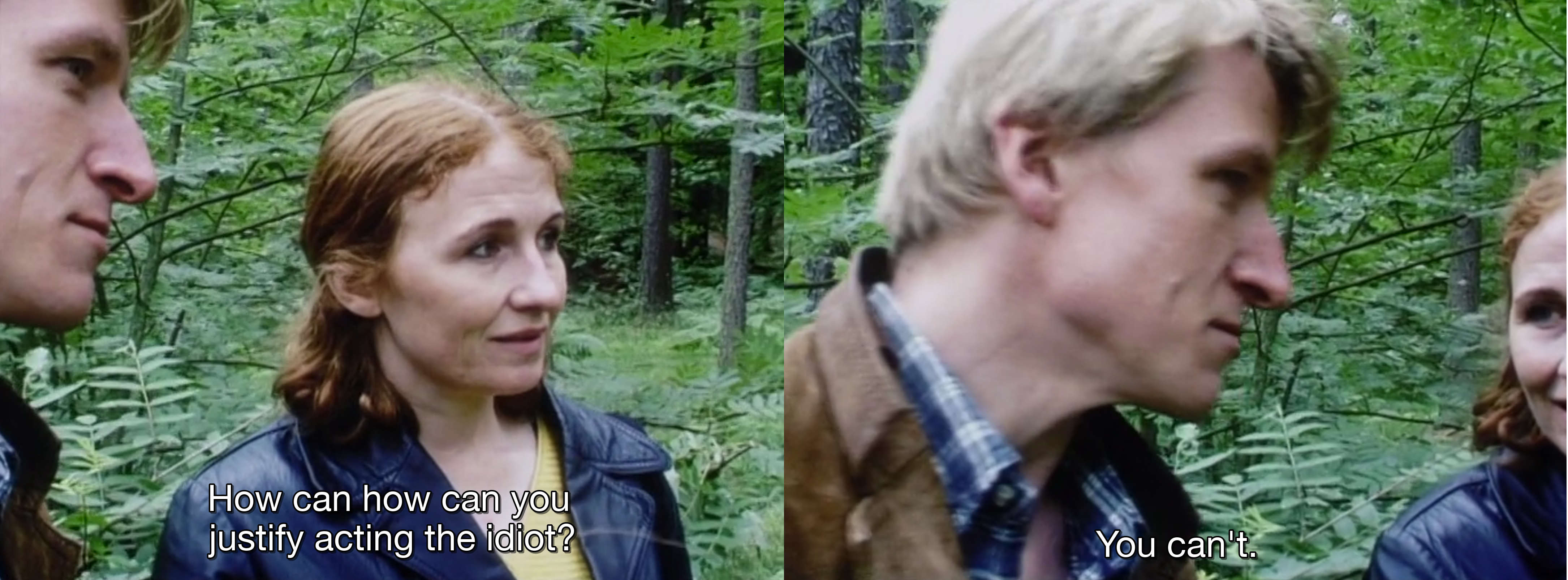

The shot cuts to the group in the corner, to a woman we come to know as Susanne (Anne Louise Hassing) – dressed in white, hair pulled back with purple and green claw clips to reveal a glowing triangle of light on her face – tending to two cognitively-impaired men. At first, she’s feeding a tall, blonde guy (whom we come to know as Stoffer). Then the two men cause a ruckus, crying for no reason, repeatedly saying “hi” to every diner, tipping over bread baskets for fun. The waiter issues an ultimatum to Susanne, a demand to keep them under control. Susanne struggles to collect and escort the group from the restaurant, diverting them from an overpriced and unpaid bill. On their way out, Stoffer (Jens Albinus) grabs Karen’s hand and won’t let go. Karen – pitying the idiot, smiling genuinely for the first time in the film – joins them outside. Contrary to Susanne’s commands – “Stoffer let go [of Karen], I’ve had enough!” – they all end up in a taxi. The leather jacket that Susanne now wears perfectly matches the taxi’s upholstery, which adds to a heavenly quality she has begun to embody. Her ability to blend in with the scenery adds to the visual sense that she’s both there and not, her beautiful head floating in the cab, hovering just above the leather. Ignoring the misbehavior of Stoffer and his pal, Susanne faces forward in the passenger seat. Everyone else is in the back. Stoffer lets go of Karen’s hand, and he and his pal stare at one another until laughter bubbles up. They break character, giggling, and apologize to Susanne – not for pretending to be cognitively impaired, but for being difficult. They took the act a little too far.

Stoffer and his pal are not cognitively impaired, they are “spazzing,” an activity they do as part of a loose collective. Each character interprets spazzing slightly differently, but it always includes some combination of losing control of their faculties and motor skills: screaming, crying, undressing, caressing strangers, drooling, and needing observation – typically from Susanne, who is often stuck (but also seems to enjoy) playing caretaker. Alongside Karen, we discover the idiosyncrasies of “the group,” as they call themselves.

The group squats in a large country house that belongs to Stoffer’s uncle, Svend, and that Stoffer has promised to sell. When Svend arrives to check on his nephew’s progress, he is disgusted to find the group sleeping on the floor, floors he laments had been waxed every day for fifty years. Stoffer tries to play it off like his comrades are hired help, there to “shine the place up a bit,” the beginning of a funny but nervous exchange. They watch Jeppe (Nikolaj Lie Kaas) push a vacuum cleaner on the patio, Jeppe’s hand bent strangely in the air. Svend says, “Interesting that you know so many craftsmen.” Stoffer, attempting to chide his uncle, says that craftsmen go to public school now. Just after this, Axel (Knud Romer Jørgensen), who Stoffer introduced as a glazier, throws a brick through the window of the shed in his morning spazz, shattering the glass. When asked about someone else’s spazzing, one group member replies, “I wasn’t watching anybody. I was trying to feel it for myself.”

We follow the group on field trips to an insulation factory and the pool – but it’s not until about twenty minutes into the film that we get a detailed conversation between Karen and Stoffer about the group’s ideology. Stoffer explains to Karen that, feeling stifled by bourgeois society, arbitrary laws, and formal etiquette, they try to tease out these mediocrities from the group’s foundational understanding of life by impersonating the disabled. Stoffer explains further: “What’s the idea of a society that gets richer and richer when it doesn’t make anyone happier? … Being an idiot is a luxury but it’s also a step forward.” Scene by scene, the group members’ individual relationship to spazzing is revealed. For Ped (Henrik Prip) it’s an intellectual endeavor, Nana (Trine Michelson) uses it to excuse her public nudity, but Susanne’s reasoning is cloudy, and her role as caretaker puts her in a position (like me) to judge the group’s validity.

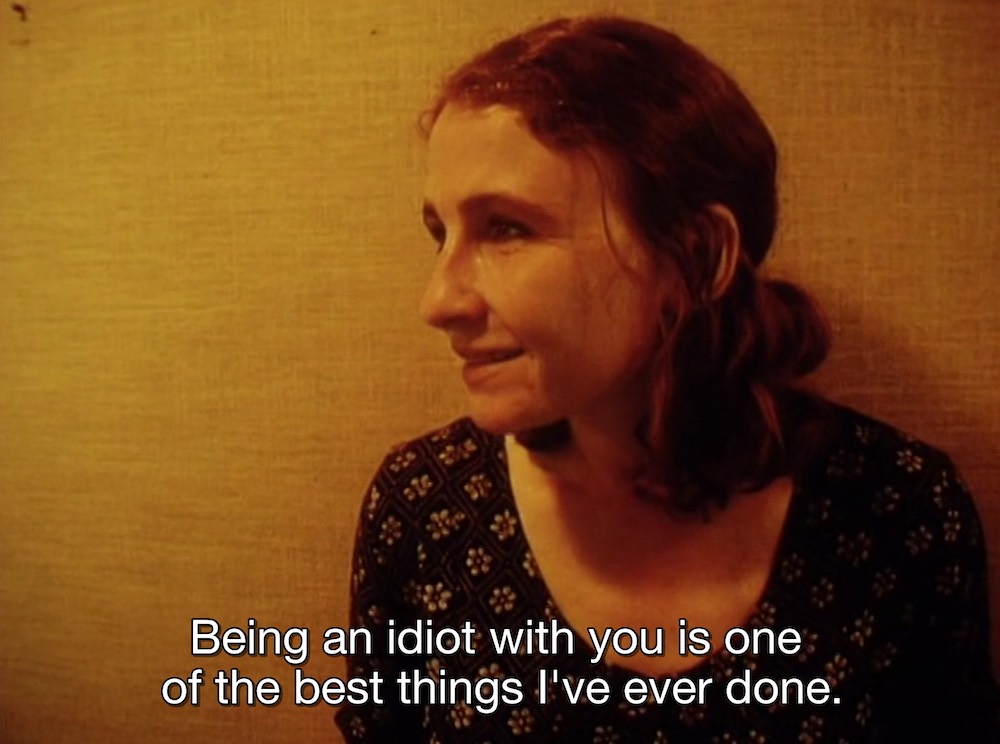

I’ve seen The Idiots twice, separated by a decade. The first viewing was startling to say the least. On a classroom projector, along with the ten other cinephiles in my international cinema class, before trigger warnings were in vogue, I was shown this film without the slightest hint as to the forthcoming content (thank you Professor Dagnan). Last year, a decade after that initial viewing, amidst on and off health issues, I watched a janky torrent of The Idiots. I balanced my dirt encrusted laptop on my hip, unable to lie flat due to the pets I’ve adopted, pets who continue to cushion the blows I receive as I plunge into my thirties. Watching a movie with my two beagle-mixes, Larry and Energy, and Marcus the cat, might complicate the experience (only so many of us fit on a loveseat) but the vital comfort these animals bring to my lickable wounds is invaluable – as anyone with animals will be panting to tell you. It took me ten years to realize, with the help of these creatures, that it’s fun being an idiot, and more pleasurable to the alternative.

It’s also important to note that the two years in which I’ve watched this film (2012 and 2022) also coincide with the two years in which I ingested LSD. I’m no hallucinogenic prude – mushrooms have made gelatin of many of my weekends – but acid is unique. Its violence is different. I was lucky enough to have two “good trips” (complete with Fear and Loathing lizards in the portajohn) but the chemical code of my bliss leaked from inside the feeling, shedding the illusion of this pleasant state, deflating it in real time. And the way in which reality crawls back in the wake of a trip – as if wounded and begging: why can’t life always feel so good – recalls the reason I need to write about it. The Idiots was one of those films that pushed me past excitement into something new, unsettled me at a time when I needed a bit of shaking up, and forced me to witness my life from the outside, like a decent drug trip without the chemical afterglow. I didn’t watch this film a second time for some nostalgic bump, but to peel back this decade-old wound, to unburden myself before you.

The Idiots, the second installment of the Danish Dogme95 film movement canonized by Lars Von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, followed many self-imposed constraints, comedically known as “Vows of Chastity,” which demanded on-location shots, natural light, handheld cameras, no filters, and no superficial action (murder, for example). Divergence from the doctrine must be confessed. Von Trier confessed in an interview that he used an offscreen harmonica player to accompany a few scenes in The Idiots, as non-diegetic music was not allowed. By eliminating special effects and studio budgets, Dogme95 was a movement that sought to restore and cleanse a director’s rawest creative power. “Every style is a means of insisting on something,” writes Susan Sontag. She insists that content is a specific stylistic convention. Although we live in an era obsessed with content (“What’s this about?”) I must agree with Sontag that the how of a work of art is as important. Artistic boundaries are always a formal excursion, even when unjustly imposed – now more than ever. Style devours content and spits back a retardedly pure art.

The movie’s most assertive stylistic decision is a formal one. The scenes at the house and around town are broken up by talking-head commentaries from members of the group. The retrospection allows the characters to reminisce and romanticize their time in Stoffer’s group, which creates dissonance between what they tell us and what we see. Prior to one of these revealing sequences, Karen questions the group’s motives, but genuinely wants to understand. “Understand what?” Stoffer asks. “Why I am here,” she says. “Perhaps,” Stoffer replies, “because there is a little idiot in there that wants to come out and have some company.” Then a couple of characters talk to the camera, mockumentary-style, about Karen: “Karen was the last to join the group…She’s right that we were poking fun…I think she would have joined anything.”

When I first watched this film in Professor Dagnan’s class, I was nineteen, depressed, and fiddling with psych meds that produced much more violent side-effects than those they claimed to curb, the pinnacle of which was sleep paralysis. I drank too much to steer my life anywhere, vomiting and blacking out often. I felt unlovable, and had trapped myself beneath the reasons why: I hadn’t been in a serious relationship, hadn’t had sober sex, et cetera. I saw the world through this very narrow pinhole and it was choking ever smaller. The combination of pharmaceuticals and recreational drugs made it difficult to widen this lens, and dragged me further away from myself. It has become clear to me, later in life, that these compulsions were just as self-destructive as when I’d purposely drag my hunting knife across my skin. This bloody ritual was a quick fix to tap the well of deeper issues. But no amount of this experimentation – sex, drugs, or self harm – provided long-lasting relief.

In addition to the international cinema class, I was taking a course in eastern religions. My great-grandmother was a Hindu, and my grandmother talked about reincarnation not as some philosophical idea but as a fact. So, as I thirstily read The Upanishads & chanted with the local Hare Krishnas, I clung to the fact that Hinduism was in my blood. Getting lost in my reading and singing (the fact that I had to be willing to be a bit of an idiot to do this is not lost on me), I began to see that there was more to life than what appeared through my narrow vision. But books and mantras only carried me so far. They were quick fixes in the opposite direction of the one I had been traveling in, which felt like a balancing act that somehow granted me further access to my personal downward spiral. The shallow escapism I experienced from singing these songs did however give me a glimpse of something deeper than the syllables on the surface, a flash in the dark – like dropping acid has been known to do for the religiously repressed. It pointed out a scab worth picking at. I needed to dig through that wound to the other side: I needed less talk and more action.

In addition to the international cinema class, I was taking a course in eastern religions. My great-grandmother was a Hindu, and my grandmother talked about reincarnation not as some philosophical idea but as a fact. So, as I thirstily read The Upanishads & chanted with the local Hare Krishnas, I clung to the fact that Hinduism was in my blood. Getting lost in my reading and singing (the fact that I had to be willing to be a bit of an idiot to do this is not lost on me), I began to see that there was more to life than what appeared through my narrow vision. But books and mantras only carried me so far. They were quick fixes in the opposite direction of the one I had been traveling in, which felt like a balancing act that somehow granted me further access to my personal downward spiral. The shallow escapism I experienced from singing these songs did however give me a glimpse of something deeper than the syllables on the surface, a flash in the dark – like dropping acid has been known to do for the religiously repressed. It pointed out a scab worth picking at. I needed to dig through that wound to the other side: I needed less talk and more action.

Cut to Stoffer’s birthday party. Before it devolves into a gangbang, there’s a poignant talking head interview with Susanne and Katrine (Anne-Grethe Bjarup Riis), another group member. We’re now a little over half-way through the film, and Katrine reflects on the inevitable dissolution of the group. She says, “I just think it’s over. I don’t think we can find the same fine things that we found there. We can’t find them again.” Then Susanne: “I was the one who was with Karen on the last day. And I was the one who said good-bye to her.” With the end in sight, the party begins. It’s not really Stoffer’s birthday, but an apology of sorts for cuffing him to his bed after he chased a city councilman nude off their property. “What? Did you think I actually went mad!” he screams. In a Dogme95 film, stand-ins were a no-no, so the naked bodies aren’t stunts. Susanne – Anne Louise Hassing – at first resisting the idea that the party should degenerate into an orgy, acquiesces and is playfully chased, then stripped of her hesitancy and clothes. “I’ll give you a gang-bang!” she says, laughing and slapping Stoffer’s chest. Then, after several shots of naked, gyrating bodies, the camera pans to Karen, who sits in a window seat fully clothed, with nobody pestering her to disrobe the way the men did with the other women. She witnesses the depravity with a sideways glance, and then she’s swallowed by the light.

The instructor of my eastern religions class also taught tai chi in a local park where the sun trickled sharply through the oak leaves. I decided to join. Training began promptly every Sunday at noon, which felt impossible when I started. To withstand Sundays, I cut partying back to one night per weekend. Life, sans amphetamines and suicidal ideation, would operate at least a little smoother. I went from making fun of martial artists at the park to swaying with the breeze. It’s a balancing act and I haven’t practiced as much as I’d have liked because tai chi is a struggle. The most difficult elements are not necessarily physical (and trust me, it’s no slow motion yogurt commercial for the elderly). The internal, self-reflective, meditative aspects bring you face to face with yourself, the world, and your place in it. If you’re lucky, you’ll retain a bit of wisdom along the way. Even now, each time I bow to the masters, I continue to realize how much work has yet to be done (I still look like an idiot), but also that there’s no need to stress, as I can only do one exercise at a time. And, each time I bow fortifies me with two opposing forces: the ability to let go of (the idea of) myself, and the self-discipline I’ve developed through training.

Stoffer imposes rules on his cult, as Von Trier does with his film, as I have learned to with my life. The Idiots is about discipline as much as it is about anything. Not only the discipline of the characters, but of the director upon his actors. In the climax of the film Stoffer makes a challenge to the group, “If you can go back to your families or jobs and still be a spazzer, I’ll believe that you’re serious. None of you have the guts.” A game of spin the bottle chooses Axel to go first: to spazz in his life outside the commune, at the school where he used to teach. But when he goes back to work and stands in front of the school board, he can’t bring himself to do it. There is a potent suffering, one that Axel and the other posers in the group are unwilling to embrace, brought on by ego-death, or a loss of sense of self, that might come from spazzing in an uncomfortable environment. His intellectual nature prevents him from letting himself go. He’s not able to adhere to (what could be) a mantra of the group: less talk, more action.

Hollywood actors often impersonate the disabled to build cheap sympathy between audience and protagonist (Forrest Gump, Rain Man, I Am Sam). But it’s not The Idiot’s controversial content that makes the film compelling, it’s the film’s formal restrictions. In several shots, the boom teabags Von Trier’s mise-en-scène. The shaky handheld gives the film a porno aesthetic, creating a pleasant doubling, the audience hyper-aware of the meta reversal of the art being simultaneously addressed and portrayed. I’m reminded of a passage from the Mandukya Upanishad: Two birds, inseparable companions, perch on the same branch. One bird chirps, eats worms, and does all the things that a bird does while the second bird watches the first bird doing all of that. It’s an analogue for the two parts of the self – the doer and the observer. We can’t have one without the other. The doer and the observer coexist like a tai chi symbol in Susanne. She is the group’s perpetual trip sitter, the core around which the idiots spiral.

Between viewings, my general feelings about the group have changed. At first I venerated them for being a middle finger to society, then I pitied them, recognizing the pain it takes to upend one’s life and join a cult. I’ve gravitated away from both of these feelings toward a middle path, in part because my immediate identification has shifted from Karen (in the search to quench her pain) to Susanne (in her embodiment of discipline and chaos). Likewise, I find the group both valid and perverse. They’ve stumbled upon a method of unshackling the ego, and while most group members will remain phonies and never fully take advantage of this tool, even the phonies are in pain for which spazzing offers an escape. Time spent with my dogs (our tongues dragging behind us, panting, howling at the moon) or practicing tai chi in the park (arms and legs flailing) proves the value of letting myself look like an idiot.  Like my two viewings of this film, the twin LSD trips I’ve taken gather power from each other, even after the experience is (supposedly) over. I remember coming up on the second hit, lines in my palm wavering, touring the root of who I was: becoming less like Karen, more like Susanne.

Like my two viewings of this film, the twin LSD trips I’ve taken gather power from each other, even after the experience is (supposedly) over. I remember coming up on the second hit, lines in my palm wavering, touring the root of who I was: becoming less like Karen, more like Susanne.

Leonard Cohen sang: “Suzanne takes you down to her place near the river...And you know that she’s half-crazy / But that’s why you want to be there.” His song fits our Susanne like a snug dress. Even in a group of idiots I would say she’s only half-crazy, as she experiences the group’s tears and laughter without ever explicitly spazzing. It’s enough for her to be there. Nearing the end of the film, the cult is dissolving and Karen sends everyone off with a benediction. Karen describes Susanne: “Who smiles at everyone so that the very heavens shine down upon us.” Susanne knows that spazzing is a game. She also knows that Stoffer doesn’t think so. She is able to balance two contradictory truths and live in relation to nuance. She knows that she doesn’t have the whole picture, and that she won’t have the whole picture until the very end. In this emotional climax, Karen accepts Stoffer’s challenge to uncover a new part of herself, to let out her inner idiot not just in the safety of the commune, but somewhere that really matters. Karen says, “It is my turn to go home and see if I can be an idiot there…We’ll see if I can show you that it has all been worthwhile.”

Karen and Susanne journey to Karen’s family home, where her relatives are not pleased to see them. In the kitchen Karen’s sister tells Susanne, “We haven’t seen [Karen] for two weeks. Anders and Karen lost their little boy. It probably hurt Anders most. What with [Karen] just disappearing and not attending the funeral.” Susanne finds Karen clutching a baby photo, a hand over her mouth, weeping. All of the clues collide as we learn that Karen is grieving the loss of her young boy, and that this profound emotional experience is what broke her open to go along with an idiot’s invite. Up until this point, the spazzing seems like a game, or at the very least has an element of playfulness to it, but spazzing was never a game for Karen. Grief looks different on everyone. For Karen, it takes the form of pretending to be an idiot, which she does, successfully, painfully, surrounded by three generations of her family. As they all sip coffee and eat cake, Karen begins to drool, yellow mush smeared across her chin. Some family members stare at Karen while others purposely look away. Karen’s husband, after making it clear he doesn’t think Karen cares about the death of their son, slaps her. Karen screams, her lips tremble and all her coffee spills down her face and onto her stained and wrinkled dress. Susanne stands and says, “That’s enough now, Karen,” and takes her hand, and leads her toward the door.

Time dissolves its blotter, shirking the past, smearing the future bright and dumbly wide open. Like a supernova, Susanne is there until the very end, even after the explosion. She holds everyone together as long as possible but, like an acid trip or the commune, the film must end. Susanne’s is the last face we see before the credits roll. May we learn to bear witness to both ourselves and others, and may we understand when it’s time to go, like Susanne.

David Kuhnlein lives in Michigan. He is the author of Die Closer to Me (sci-fi/ horror), Decay Never Came (poems), and a collection of horror film reviews: Six Six Six. He edits the book review column Torment, venerating pain and illness, at The Quarterless Review. He recently acted as Vincent Gallo in a short film. Attempting to share the film with Gallo, his email subject line read: GRADE B MAPLE SYRUP & BOYD RICE, but he has yet to hear back.

David Kuhnlein lives in Michigan. He is the author of Die Closer to Me (sci-fi/ horror), Decay Never Came (poems), and a collection of horror film reviews: Six Six Six. He edits the book review column Torment, venerating pain and illness, at The Quarterless Review. He recently acted as Vincent Gallo in a short film. Attempting to share the film with Gallo, his email subject line read: GRADE B MAPLE SYRUP & BOYD RICE, but he has yet to hear back.

~